|

The New Luther Movie By Pastor Marshall

"Luther," the new $30 million German-American co-produced movie, opened in 400 American theaters nationwide the first week of October. It stars Joseph Fiennes as Luther and Sir Peter Ustinov as Prince Frederick the Wise, Luther's protector and friend. It covers Luther's career from his decision to enter the monastery on July 2, 1505 until the Augsburg Confession of 1530. Luther lived from 1483 to 1546 so this movie covers less than a third of his rich, faithful life. Susan King of the Los Angeles Times writes that this movie "filters" the religious commitments of Luther "through political ramifications" (The Seattle Times, October 9, 2003). As such Luther comes off in the movie as a social reformer who changes the western world by standing up against the giant organizational power of the Roman Catholic Church. While this is a beautiful and well-made movie, it's political filter distorts Luther. He was above all a teacher of the Bible who loved his church. But that doesn't come through well. This movie instead trades political sensation for religious detail. It has Luther nailing his 95 Theses against church corruptions on the church doors, October 31, 1517 – something which his famous biographer Martin Brecht explained long ago he never did. But it makes for good film footage. So too his sympathy for the peasants' rebellion is overblown – which it must be if Luther is construed as a social reformer. His sorrow over little Greta is a case in point in this movie. While Luther thought mercy should be shown to peasants who surrendered, the rest he said should be killed outright. No Marxist revolutionary here! The movie also inflates Luther's defense of the gospel. It doesn't combine it with his love of the law and his healthy fear of God's wrath. When Luther struggles over God's will for him he writhes on the floor, twitching as if insane. The producers of the movie appear to have taken to heart, the potboiler, Young Man Luther: A Study in Psychoanalysis and History (1958, 1962) by Erik H. Erickson. Luther's reports of anxiety were more cerebral than incapacitating. In spite of it all, he was still able to cope with his difficulties and many responsibilities in life. He wasn't a nut-case as this movie suggests. There are also other mistakes. When translating the New Testament at the Wartburg the movie has Luther say that the words of the Bible don't matter as much as the meaning we give them. But he didn't believe that. He was a man of the actual text of the Holy Scriptures. All reliable Biblical meaning comes from those words so he cherished them. Prior to the Augsburg Confession Luther visited the new Lutheran parishes in Saxony. He was disgusted with the moral and theological corruption he found. To combat this mess, he returned to Wittenburg and wrote his catechisms. They were designed to correct the errors he saw in the churches he visited. This problem made him less optimistic than the movie portrays him in 1530. Nothing about the visitation and catechisms appears in this movie – something dear to all Lutherans. Apparently the catechisms don't make for good movies. The movie also levels an inordinate attack on the Roman Catholic Church. At one point it has Luther joking about St. Cyprian's (200-258) famous dictum that outside the church there's no salvation. It has Luther say you can have the Savior without the church. But he didn't believe that. He knew you could only find Christ in the church where faithful preaching and the sacraments are received. All he said was that the Roman Catholic Church didn't have a corner on the church. The church is wherever true believers hear the word of God and celebrate the sacraments faithfully. All in all, Luther thought most of the Roman Catholic Church good. What was needed was fine tuning on a handful of issues including celibacy, indulgences and the sacrifice of the Mass. The movie also errs in making Luther’s marriage to Katherine more romantic than it was. Its fascination with sex is out of place. Along with its excellent visuals and superb editing, there is one scene in the movie that is very good. This is when Luther gives his German translation of the New Testament to his prince, Frederick the Wise. Even though this didn’t actually happen, since it was George Spalatin who delivered it, the scene is still moving. It shows how hungry people were to have the Holy Scriptures in their own tongue so they could study them again and again. Adding up the pluses and minuses I can’t recommend this new movie on Luther. (Reprinted from The Messenger, November 2003.)

|

|

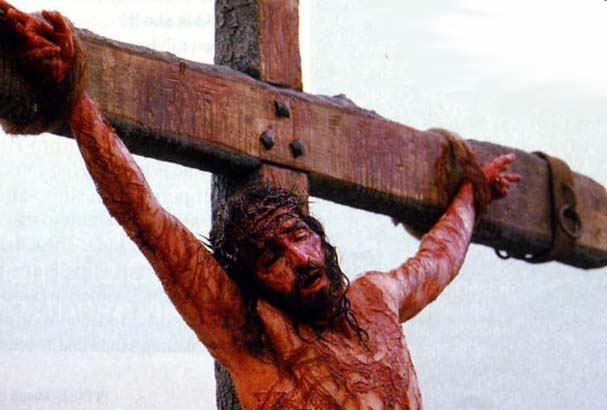

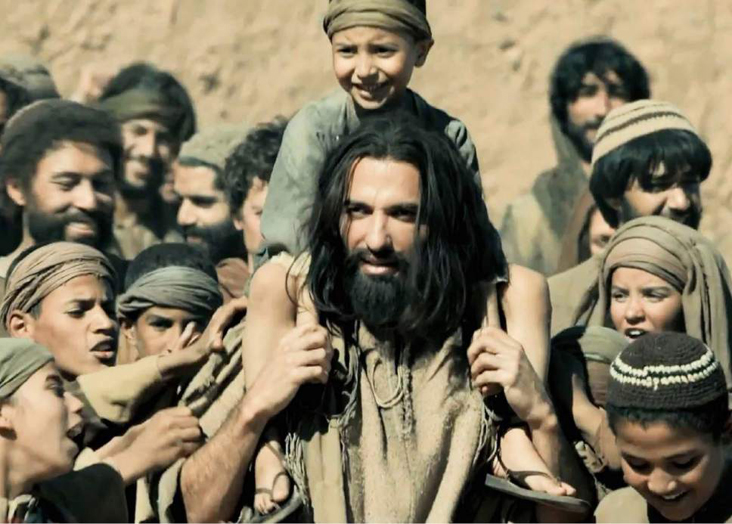

Suffering for the Sins of the Whole World __________________________________________________________________________ The Gospel According to Mel Gibson By Pastor Marshall How would you show Jesus Christ saving us from the sins of the whole world by his suffering and death (1 Peter 2:24; 1 John 2:2)? Clearly the ordinary suffering of one person could not show this. It would not be extreme and excruciating enough. Mel Gibson tries to solve that problem in his new movie released Ash Wednesday, February 25, 2004, entitled The Passion of the Christ. In it he tries to make the suffering of Christ more than what one man could bear so that the saving of the whole world can be seen in what this single man had to go through. So when Jesus is nailed to the cross in this movie, it is over the top. The soldiers tug on his arm with a rope to pull it out enough to get it nailed just right. You hear bones pop under the strain. And to make sure the nails pounded in stay put, the soldiers flip the cross over, slamming Jesus down, in order to bend the nails over on the back side. And when he is whipped, the spikes on the end of the leather thongs get struck in his back and the soldiers have to yank extra hard to free them -- tearing apart his back which leaves him in a puddle of his own blood. Scenes like these could gross you out. They, I suppose, are not for everybody to see. But again, if you want to see the weight of all the sins of the world resting on one man, this movie does that in epic proportions. And if you want to be true to the prophecy in Isaiah 53:2-3 regarding Christ's repulsiveness, then not even Matthias Grunewald's Isenheim Altarpiece (1516) with its suffering, syphilitic Christ on the Cross, does a better job than Mel Gibson does. For surely in this movie Christ, in the words of Isaiah, has "no comeliness that we should look at him, and no beauty that we should desire him." He is seen as one from whom we would rightly "hide our faces." In fact, it nearly makes you vomit to watch the way Christ suffers in this movie. What I liked most about this movies was its framework from Isaiah 53:5, that Christ suffered at the hands of his Father in heaven albeit through the evils deeds of men, and that this horror or curse (Galatians 3:13) actually saves us from our sins and God's wrath (Romans 5:9). Most of the churches in America today have thrown out this message for a tamer, more intellectually acceptable one -- forged in what has been called "the messy midrash of American culture" [Stephen Prothero, American Jesus: How the Son of God Became a National Icon (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003) p. 9]. But not Gibson's The Passion of the Christ! He shows utter contempt for that tamer view when he has Jesus quote John 19:11 that neither Pilate nor anyone else ultimately killed him -- for it was God himself who did it, granting his permission "from above"! Shocking as it is to our mild, modern ears, Jesus was actually crucified "according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God" (Acts 2:23)! All the debate over whether or not this movie fuels the fires of anti-Semitism could have been avoided if this point had been duly noted. But why would God do such a thing to his only begotten Son? Jesus answers this when he tell his mother Mary on the road up to Golgotha -- quoting from Isaiah 43:19 -- "Behold, I am doing a new thing." His suffering has a purpose. He is no victim. Indeed Jesus quotes John 15:13 that there is nothing better than dying for others and John 10:17 that he has the power to do just that. In his death he makes the forgiveness of sins possible by paying the price for our sins. This death "cancels" the legal bond held against us (Colossians 2:13-14). This is the new thing he is doing. And so when Jesus dies, Gibson uses the best translation of John 19:30 and has Jesus say, "It is accomplished" -- not "it is finished." The penalty has been paid. God's wrath has been stilled. Peace between God and sinners is now possible (Romans 5:1 reversing Isaiah 59:2). This suffering death has accomplished that. Another great scene in this movie was when the devil returned to torment Jesus in Gethsemane (Luke 4:13; Matthew 26:39), saying to him that bearing all the sins of the world would even be too much for him to carry! The devil is portrayed as a spooky woman with a man's voice hovering throughout the movie only to be thrown down in hell at the end when Jesus dies. This scene reinforces the Isaian context of the entire movie. Other notable scenes were when the Temple quakes and its curtain is torn (Matthew 27:51); the tormenting of Judas which causes him to kill himself (Luke 22:3; Matthew 27:5); Simon of Cyrene's helping of Jesus on the road to Golgotha (Matthew 27:32); the raven pecking out the eye of the cynical criminal dying next to Jesus (Luke 23:39); and Jesus saving the woman caught in adultery and his dramatic writing in the dust with his hand (John 8:2-9). My only criticism of this movie is having Jesus' mother Mary say to him while he carries his cross to Golgotha that she would like to die with him. That brings her too close to being a co-redeemer which she clearly is not (see 1 Timothy 2:5; Hebrews 9:26). The movie closes with the resurrection -- from within the tomb itself -- something not even the New Testament affords us. In the darkened tomb we begin by hearing the huge stone, slowly rolling away. As the light gradually comes in, we see the shroud that covered the dead Jesus deflating as he invisibly, mysteriously comes to life. Then in a determined, purposeful profile pose, we see the resurrected Christ in his visible body, leave the tomb slowly, showing us only his wounded hand swinging at his side. What a glorious ending! He is off to begin his mighty forty days of work on earth prior to his dazzling ascent into heaven. I agree with those who have said that no greater movie on Jesus has ever been made. (Reprinted from The Messenger, March 2004.)

|

|

Debunking the Jesus Video Project Ronald F. Marshall A WORLDWIDE EVANGELICAL EFFORT to

witness to Christ has been made through the movie Jesus

(Inspirational Films, 1979)—distributed by the Jesus Video Project

of San Bernardino, California. Promoters say, "no other film has

been seen by more than one billion people, translated into more than 425

languages and shown in more than 225 countries." At the end of 1999

it is being given another big push in the But I for one will not cooperate. Even though I am for witnessing to Christ in my homeland, I do not believe this video is the way to go. This is because the video intentionally misrepresents Jesus by chopping off Bible verses, inserting untrue material, and by dropping entire key Bible verses. Because of that deceit all Christians should join me in debunking it. If you must witness to Christ by means of a video, find another one. In his posthumously published book, Opening the Bible, the esteemed Thomas Merton (1915-1968) recommended the 1965 movie by Pasolini, The Gospel According to St. Matthew. It has its problems but it is better than what the Jesus Video Project offers. The movie from the Jesus Video Project manipulates viewers into thinking Jesus is nicer than he was and is. It assiduously works to eliminate what may succinctly be called "the wrath of the Lamb" (Rev. 6:16). This will surprise many who have seen and praised the movie. They will point to the crucifixion scene where Jesus screams as the nails are being graphically pounded into his body. But this segment is pure sentimentality! It wants to bring us to tears over the brutalizing of a nice guy. The crucifixion, however, was about other matters. In addition to the abandonment of Jesus by God the Father it wanted to shock us by the human violence Jesus' offensiveness provoked. The reason for this cinematic soft-pedaling of Jesus is fairly obvious. The movie so desperately wants to convert the world to Christ that it willingly misrepresents him so he no longer is "a stone that will make men stumble" (1 Pet. 2:8). Because this movie wants to win the entire world for Jesus it feels justified in revising the offensive picture painted of Jesus in the Bible. But conversions based on these changes are wicked because they deceive. They draw people to a phony Jesus. Consequently the makers of this movie are like the scribes and Pharisees of old who "traverse sea and land to make a single proselyte" and when they do have only made him or her "twice as much a child of hell" (Matt. 23:15) as they themselves have become! The movie follows fairly closely the Gospel according to St. Luke. Early on the deceit begins. When Jesus' mother praises God for choosing her, the excerpts picked from those famous verses skip the need to "fear" God and his startling "put down" of the powerful (Luke 1:50, 52). Also, when John the Baptist says that Jesus will "gather the wheat," the end of that verse about burning up the chaff with "unquenchable fire" is cut off (Luke 3:17). On either side of this last verse important words are also dropped. That Jesus is "set for the fall of many" (Luke 2:34) and that his first sermon provoked "wrath" (Luke 4:28-29) are skipped. Consequently when Jesus shortly thereafter says that we should "rejoice" when people "hate" us on his account, it dangles meaninglessly. By intentionally removing Jesus' provocation, the hatred seems flighty and less horrifying than it should be. So when Jesus' words about blessing those who refuse to be "offended" at him (Luke 7:23) are changed into blessing those who do not "doubt" him, we see what this movie has been about. "Doubt" is much softer than "offense." This movie has been trying to make Jesus easier to believe in than the Gospel does. For doubt is easier to overcome than being offended. Puzzlement can be set aside in ways that hurt feelings cannot. Grudges last far longer than quandaries. This movie knows that and wants us erroneously to think the same. Continuing in this vein, when Jesus exorcises the Gerasene demoniac by transferring his demons into a large herd of pigs, the fact Jesus then "drowned" this herd in a nearby lake is cut out (Luke 8:33). But without this seemingly unjustified destruction of property the people's "great fear" (Luke 8:37) comes off as frivolous. We also miss out on learning about the cost in having Jesus among us! We also miss out on that cost when the movie turns "denying" ourselves for the sake of Jesus (Luke 9:23) into just forgetting ourselves. This revision breaks the link to Jesus' even harder yet similar word that we should "hate" our "own life" as well (Luke 14:26). This is an especially clear instance of the way that this movie falsifies Luke's Gospel. No wonder it also ignores Jesus' warning that belief in him will pit family members "against" each other and split up households (Luke 12:51-53)! Such a message will not attract young families. It is too offensive. But in the name of evangelism this movie says: “To hell with the truth!” So too regarding the devil's attack on Jesus' disciples. The movie rightly reports that Satan "entered into Judas" (Luke 22:3) but refuses to say the same of Peter who was also "sifted" by the devil (Luke 22:31). The movie begins its reporting two verses later. This revision illegitimately limits the haunt of the devil to the crackpot Judas. This change inchoately promises false security to new converts. This lie is reinforced by dropping the verses about an exorcised man being quickly invaded by seven new demons "more evil" than the first who make his life "worse" than before he was first exorcised (Luke 11:26). Think how offensive this vulnerability makes the healing hand of Jesus! The cure comes off worse than the disease. But this movie will have nothing of this truth about Satan and his demons. Why? It will scare off potential converts to Jesus! So much for the truth! This movie would rather have the disciples look like heroes so that potential converts would want to join. Accordingly, after Jesus "drives out" the merchants from the temple (Luke 19:45), it inserts shots of his disciple holding back guards set to restrain him. But the New Testament itself never lists any such heroic deeds! Again the truth goes begging in order to make Jesus look more attractive than he was so people will believe in him. Perhaps the most

egregious deception in this movie is the blatant bastardization of the

weeping women at Jesus' crucifixion. On the way to Finally, at the end, the negative response of the apostles to the women's report that Jesus was raised from the dead is also cut out. They did not believe because the words "seemed to them an idle tale" (Luke 24:11). An idle tale? These burning, cynical words are too dangerous to report. Others may think the same, after all. They provide too easy a way out. They must be silenced. This movie thinks it's a bad idea to get its viewers wondering why those closest to Jesus thought the triumph of his life was just an idle tale. They want it to come off more victorious so people will want to come along. This movie wants to rush to the "great joy" at the end (Luke 24:52) without first passing through cynicism and “disbelief” (Luke 24:41). In the Gospel according to Luke Jesus presses potential believers to "count the cost" of believing in him (Luke 14:28). Because this movie intentionally and faithlessly reduces this cost by making Jesus nicer than he was and Christian discipleship easier than it is, it should not be used for evangelism. Holding as it does that Jesus is the Son of God, who died for our sins and was raised bodily from the tomb, is not enough to commend it. For in the process of developing this message cinematically the light of this faithful word is turned into "darkness" (Luke 11:35). (Reprinted from Lutheran Forum, Winter 1999.)

|