|

For

Christians Only

By

The Rev. Ronald F. Marshall

First

Lutheran Church of West Seattle,

WA

February

2005

1. Only Christians Go to Heaven.

The Bible says there is salvation in "no other name" than that

of Christ Jesus (Acts 4.12). It teaches that if we don't believe in

Christ and obey him, "God's wrath rests upon us" (John 3.36).

This wrath brings the horrors of "eternal destruction and exclusion

from the presence of the Lord" (2 Thessalonians 1.9; Matthew 25.46)

in a "place of torment" (Luke 16.28). In this "outer

darkness" there will be "weeping and gnashing of teeth"

(Matthew 25.30). It surely won’t be a place to go to party with all

our rebellious and carefree friends.

Only belief in Christ can save us from this torment because he

alone brings us the grace of God the Father (John 14.6). So if we love

Christ Jesus, the Father will then love us and save us (John 14.21).

This is because Jesus dies for us (John 10.17) and offers up his life as

a sacrifice for sin to the Father (Ephesians 5.2). No one else can do

this for us (1 Timothy 2.5; Hebrews 9.26). He is the pure sacrifice (1

Peter 1.19). His death pays the penalty for our sin (2 Corinthians 5.20;

Colossians 2.14) and makes peace with God (Romans 5.1; Colossians 1.20).

When we accept this sacrifice and entrust our well-being to Christ our

Lord (Romans 3.25, 6.22, 10.9), we are saved. Otherwise, we are lost (1

John 5.10-12). So salvation comes only "through faith"

(Ephesians 2.8).

2. Only a Few Believers.

How many believe this? Jesus hoped at least some would (Luke 18.8; 1

Peter 5.18). He knew it was "offensive" and that most would

cast it aside (Matthew 11.6; John 6.61). This was largely because it was

based on his gruesome, agonizing, repulsive death (John 3.14; 12.32). So

only a "few" would end up believing (Matthew 7.14, 22.14).

Just a "remnant" would take it to heart (Romans 9.27). And

even they would only go kicking and screaming – if you will (Romans

9.16-18; Acts 9.3-9; 14.22; Romans 6.4). Even among those who say they

are Christians, many actually are not – Luther estimated upwards to

90% are phonies (LW 23:398-400)! And this small number with its terrible

consequences makes quite clear the "severity of God" (Romans

11.22; Hebrews 10.29). Oh, what a "fearful thing it is to fall into

the hands of the living God" (Hebrews 10.31). Indeed, God Almighty

is to be feared (Matthew 10.28).

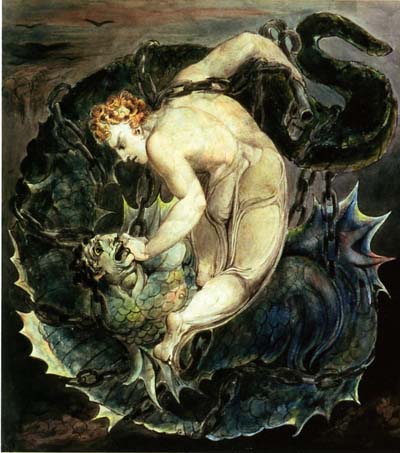

3. Scared

Away By Suffering. Christianity – when first believed – appears

to be filled with joy (Luke 2.10 vs. Luke 12.49-53). But when we realize

that suffering with Christ is also required (1 Peter 4.13; Romans 8.17;

Matthew 16.24), we fall away (Matthew 13.21; Galatians 1.6). This

suffering includes being vilified for Christian truths (2 Timothy 4.1-5;

1 Corinthians 1.18). Luther called this contestable, unpopular truth, aspra veritas or "rough truth" (LW 11:58) and even

something "absurd" (LW 16:183). Most don't want the

embarrassment of this. All we want from Christianity is a "belly

sermon" that will "enrich" us in worldly terms (LW

23:5,11). So if Christianity were free of suffering, many more would

sign-up. But it isn't, so only a few love Jesus with a "love

undying" (Ephesians 6.23). These are called the foolish ones (1

Corinthians 4.10-13).

True salvation only comes with "fear and trembling"

(Philippians 2.12). So the "Christian life is nothing else than....

incessantly... purging out whatever pertains to the old Adam [who is]

irascible, spiteful, envious, unchaste, greedy, lazy, proud... and

unbelieving." Without this "earnest attack on the old

man," our faith is "hollow" (The

Book of Concord, p. 445; LW 26:269). This is because the freedom

faith brings (2 Corinthians 3.17) doesn't belong to the flesh. It's only

in our hearts – unseating the guilt for our sinfulness. So the battle

must rage. The hammer of God's Law must strike us hard and repeatedly

(Jeremiah 23.29; LW 26:310). For "the Law has dominion over the

flesh, but the promise [of the Gospel] reigns sweetly in the

conscience" (LW 26:301).

4. Historic,

Biblical Salvation Affirmed.

In the Lutheran Confessions (1580) these Biblical teachings are

affirmed. They teach that Christ will "give eternal life and

everlasting joy" to those who believe in him, but "hell and

eternal punishment" to those who don't (The

Book of Concord, Tappert ed., p. 38, AC 17:3). Faith in Christ alone

saves us from this doom. For he alone "has snatched us poor lost

creatures from the jaws of hell... and restored us to the Father's favor

and grace,.... not with silver and gold, but with his own precious

blood," through which he has made "satisfaction" to God

by paying what we "owed" (The

Book of Concord, p. 414, LC 2:30-31).

The Roman Catholics however aren't as clear about this. In the Catechism of the Catholic Church, (1999), it says Jesus Christ

"alone brings salvation" (§432), but under special

circumstances one can be saved if he "does the will of God in

accordance with his own understanding of it" (§1260). The same

goes for the August 6, 2000 Papal Declaration Dominus

Iesus. It says that the

Church

of

Christ

is not "one way of salvation alongside... other religions" (§21),

but that in other religions "salvation in Christ is accessible

by... grace" when Christ "enlightens them in a way which is

accommodated to their spiritual and material situation" (§20).

This is a too costly qualification!

5. Overhauling Heaven.

In the face of historic, Biblical salvation, there remain Christians

today asking for a change.

They want the church to say that all good people go to heaven whether

they believe in Jesus or not. Some are even asking that everybody be

allowed to go. This is because the wicked need mercy and purging too.

Besides, being tortured for

eternity is much too long. These views are carefully, clearly and

briefly presented of late by Jacques Ellul in chapter 14 of What

I Believe (1989), by Richard John Neuhaus in chapter 2 of Death

on a Friday Afternoon: Meditations on the Last Words of Jesus from the

Cross (2000), and by Bishop Kallistos Ware in chapter 12 of The Inner Kingdom (2000). This requested change is called

Universalism [Universal Salvation?

The Current Debate (2004), eds. Robin A. Perry & Christopher H.

Partridge].

It is clearly gentler and kinder. Damnation makes Christianity

morally and intellectually untenable. The renowned Sir Bertrand Russell

thought damnation was "a doctrine of cruelty" that discredited

Christianity [Why I am Not a

Christian (1957) p. 18]. Universalism makes more sense by being

closer to how ordinary punishments work. Only the guilty are punished

and for no longer than a lifetime. It also picks up on those few verses

that seem to be universalistic (1 Corinthians 15.22; 1 Peter 4.6; 1

Timothy 2.4).

Finally it also honors the first covenant God made with the Jews,

thereby providing for their salvation apart from belief in Jesus as Lord

and God (pace John 20.28). The

American Catholic Bishops have submitted a draft statement on this

point, declaring an end to any plea for "the conversion of the

Jews," simply because in Judaism they "already dwell in a

saving covenant with God" ["Reflections on Covenant and

Mission

," Origins (September 5,

2002) pp. 220, 221].

6. Using

Wrong Presuppositions. Opening up heaven to more than Christians is

certainly kind-hearted and open-minded. But that doesn’t justify it.

Universalism errs the way it begins. It assumes kindness and generosity

are supreme. But for Christianity this is not so. Other qualities matter

more. Distress is one (Romans 8.18). So are punishments (Hebrews 12.10),

suffering (Romans 5.3), loss (Matthew 16.23), trials (1 Peter 1.6),

tribulation (Acts 14.22) and sorrow (John 16.20). This surprising view

is derived from the centrality of Christ's crucifixion (John 12.32; 1

Corinthians 2.2). Following that conviction, the true "treasury of

Christ" is not the absence of conflict and pain but the

"impositions and obligations of punishments" (LW 31:227).

Without these prior, superior qualities in place, Christian love

– that is kindness and generosity – degenerates into "stupid

affection" (LW 13:153). So faith and truth must always be placed

high above love in Christianity (LW 26:103; 27:38; 23:330; 1:122).

Illustrative of this most contentious point, note the lack of affection

for the young rich man in Mark 10.22-23, for the damned rich man in Luke

16.24-31, for the lying Ananias and Sapphira in Acts 5.1-13, and for

idolaters in Deuteronomy 13.8.

7. An Old Heresy.

Universalism is not new. Early on Origen of Alexandria (185-254) in his

famous treatise On First

Principles, argued for Universalism only to be condemned in 553

because of it in

Constantinople

at the Fifth Ecumenical Council. He believed in Universalism because

“from [the original indestructible unity of God and all spiritual

essence] it necessarily follows that the created spirit after fall,

error, and sin must ever return to its origin, to being in God" [A.

von Harnack, History of Dogma (1900) II:346]. This necessary restoration of all

people to God is because there are no deep and durable fissures in the

world that would keep the condemned from enjoying God's blessings

forever. So for Origen this indestructible unity must result in

Universalism.

This idea comes more from Neoplatonic philosophy than from

Biblical testimony. In the Bible we see the fissure between light and

darkness (Luke 1.79) replicated permanently in that "great fixed

chasm" between heaven and hell (Luke 16.26). For this reason

Origen's view is wrong albeit wistful. It is not true that "in the

end all the spirits in heaven and earth, nay, even the demons, are

purified and brought back to God." But Origen knew the church would

never go along with this. So he called it an "esoteric"

doctrine and concluded: "For the common man it is sufficient to

know that the sinner is punished," albeit only for a short while (Harnack,

II:378). Origen may then well have agreed with Christian Gottlieb Barth

(1799-1862): "Anyone who does not believe in the universal

restoration is an ox, but anyone who teaches it is an ass" [Jaroslav

Pelikan, The Melody of Theology (1988) p. 4.].

Well before Origen, God's people also challenged his fairness. In

Ezekiel 18.25 we read: "Yet you say, 'The way of the Lord is not

just.' Hear now, O house of

Israel

: Is my way not just? Is it not your ways that are not just?'"

Similar lines are in Romans 3.5 and 9.14 with the same results. We don't

know enough nor are we good enough to improve upon God's ways among us.

8. Not All Are Saved in

the Bible. Universalists argue that Acts 4.12 is about physical

healings and not eternal salvation. They say that the word

"salvation" can also mean healing. They also note that Acts

4.12 builds on the healing of the lame man in Acts 3.7. So the whole

passage is "far removed from whether there is any 'saving'

revelation of God outside Jesus" [John A. T. Robinson, Truth

Is Two-Eyed (1979) p. 105]. But this is not so for two reasons.

First there is still the exaltation of Christ even if it is only a

physical healing. And secondly the two – healing and saving –

actually go together: the lame man was healed because of his faith in Christ (Acts 3.13-21, 4.4).

Universalists also point to Bible verses that say all will be

saved, or all

Israel

at least will be saved (Romans 11.26). But this is not true. You cannot

pass over faith when it comes to salvation. So, as Luther pointed out,

these passages only mean that "God gives both [the ungodly and the

godly] the light of the sun,.... but He does not save the

faithless" (LW 28:262; 25:431). There is no salvation without faith

in Christ, for "God himself cannot give heaven to him who does not

believe" (LW 32:76). So regarding the salvation of the Jews, that

too must come only through faith in Christ Jesus. For "the Old and

New Covenants are not two... equal, parallel paths to salvation"

[Roy H. Schoeman, Salvation is

From the Jews (2003) p. 353].

God therefore doesn't save groups of people all together at once.

He saves people individually because of their faith in Christ Jesus.

Just as we must die by ourselves

– no one can do that for us, of course – no one else can believe for

us either (LW 51:70; 45:108). So there are no exemptions or

substitutions for individual believers believing. Jesus, remember,

praised the faith of an individual over that of an entire nation:

"Not even in

Israel

have I found such faith" (Matthew 8.10).

9. All Religions Aren't

Equal. We should not expect what Robley E. Whitson has called in his

book, The Coming Convergence of

World Religions (1971, 1992). The differences between Christianity

and other religions matters to Christians. Acts 14.15 tells followers of

other gods to "turn from those vain things to a living God."

What makes these other ways useless and vain? It’s that they

cannot give us everlasting life. Nothing more. For they may still have

limited, moral value for

Christians. Indeed, "we find in the religions an echo of God's

activity in all expressions of life because God has not left himself

without a witness among the nations (Acts 14.16-17), which means that

the reality of God and his revelation lie behind the religions of

humanity as anonymous mystery and hidden power" [Carl E. Braaten, No

Other Gospel: Christianity Among the World's Religions (1992) pp.

67-68]. So Christians, for instance, are authorized to work with other

religions on matters of "world peace, human rights, cultural

enrichment, religious tolerance and care for the earth" (Braaten,

p. 99).

Studying, then, the exotic naturalistic religions photographed

and described in Wade Davis' stunning book, Light

at the Edge of the World: A Journey Through the Realm of Vanishing

Cultures (2001) has its place. So does Martin Luther's help in

getting Theodor Bibliander's 1543 Latin translation of the Koran

published along with his preface for it even when he condemned Islam

itself (Word & World,

Spring 1996). Studying other religions doesn't mean there's salvation

to be found in them. Nevertheless it remains better to know them than

not. For ignorance isn’t bliss (1 Peter 2.15).

10. Boasting in Christ.

Just because there's no salvation outside of Christianity, it doesn't

mean Christians should be arrogant about it and ridicule other

religions. Humility instead is to mark our lives – not pomposity (1

Peter 5.5). "Do nothing from... conceit, but in humility count

others better than yourselves" (Philippians 2.3). Buddhists, for

instance, may be more devout than Christians. They may take their

religion more seriously. That should be acknowledged if true. Jesus

seemed to do so, urging "making friends" even with the

unrighteous ones (Luke 19.6).

Even so we must never be embarrassed or ashamed of Christ (Luke

9.26). He is the Lord and Savior. He is the only mediator (1 Timothy

2.5) and advocate we have (1 John 2.1). So in him we are to boast –

though never of ourselves too for

believing in him (Galatians 6.14). Whatever arrogance, then, we may

have, it cannot be for ourselves. It must rather be an "arrogance

of the Holy Spirit" (LW 24:118). This is an arrogance that gives

all the glory to God (1 Corinthians 10.31). It is right for Christians

to do just that.

11. Praying for

Unbelievers. We shouldn't castigate unbelievers. We shouldn't ever

gloat over their condemnation and coming misery. "Do not rejoice

when your enemy falls, and let not your heart be glad when he

stumbles" (Proverbs 24.17). Instead we should pray for their

redemption. We should pray that they may be saved even "contrary to

nature" (Romans 11.24).

Even though we know only a few will be saved and that it all

depends on God's mercy, we should nevertheless pray for unbelievers

(James 5.l6). But isn't this against God's will? No. He expects us to

have mercy on others as God himself has had mercy on us (Ephesians

4.32).

St. Paul

even was ready to give his salvation away to the damned that they might

be saved instead of him (Romans 9.3). So our prayer should be: “Have

mercy on those who do the devil's bidding. Crush their hearts and bring

them to repentance and faith in your dear Son, Christ Jesus, that they

may know the joy of your salvation. Nevertheless, thy will be done

(Matthew 26.39). Amen.”

This prayer is not limited to men, the wealthy and politically

free (Galatians 3.28). Neither is it limited to certain ethnic groups

(Acts 10.35; Matthew 28.19). Christ after all truly died for the sins of

the whole world (1 John 2.2; 1 Peter 2.24).

12. Shaming the Wise.

Believing in the unique salvation of Christ Jesus is not based on

plausibility (1 Corinthians 2.4). It isn't for the wise whom God has

shamed with his offensive word (1 Corinthians 1.27). It isn't a coherent

philosophy of life (Colossians 2.8). It’s rather based on heavenly

(Philippians 3.20) standards of possibility (Luke 1.37; 18.27) and

goodness (John 6.27). Intellectual respectability isn’t the right

measurement.

So rather than discussing God's salvation and assessing it, we

are to hear it and keep it (Luke 11.28). Any intervening interpretative

or evaluative stage in between the hearing and obeying is ruled out. We

are to take the message in like an infant does her mother’s milk (LW

16:93). No discussion, critique or revision. Just take it straight. In

this simple, primitive faith is power to be come children of God (John

1.12) – to be born from above (John 3.3). It turns us into new

creations (2 Corinthians 5.17). It makes us faithful unto death

(Revelation 2.10). Bickering about Christianity puts an end to this new

creation. And so we know why Jesus says he's not for the wise and

understanding (Matthew 11:25-27). If you can't take him in with a

childlike mind, you'll never believe in him (Matthew 18.3). This trust

is the life of the Spirit in Christ Jesus (1 Corinthians 2.13).

There is so much more about Christianity besides damnation that

is offensive. The list is nearly endless: Keep the old faith (Jude l.3),

A message without human origin (Galatians 1.12), I'd rather be dead

(Philippians 1.23), Virginal conception (Luke 1.35), Homosexual behavior

is wrong (Romans 1.27), I don't live my life (Galatians 2.20), Be

heavenly-minded (Colossians 3.2), Christ is better than anything

(Philippians 3.8), Blood relations aren't family (Mark 3.35), Rejoice

always (Philippians 4.4), Serving only God (Luke 4.8), I can do all

things (Philippians 4.13), Pray constantly (1 Thessalonians 5.17), Even

lustful looks are adultery (Matthew 5.28), Awards are bad (John 5.44),

Rejoice when hated (Luke 6.23), Care nothing about food or clothes

(Matthew 6.25), You must drink Jesus' blood (John 6.53), The tough way

is best (Matthew 7.14), The dead live (Luke 7.15), Pleasures are bad

(Luke 8.14), The sighted must be blinded (John 9.39), Let the dead bury

themselves (Luke 9.60), Threatened by wolves (Luke 10.3), Healing makes

things worse (Luke 11.26), Don't cry until bloodied (Hebrews 12.4),

Divided families are good (Luke 12.51), Hate yourself (John 12.25),

Renounce everything (Luke 14.33), Human praise is bad (Luke 16.15), Pick

up serpents (Mark 16.18), Deny yourself (Matthew 16.24), We are

worthless (Luke 17.10), Keep praying even when ignored (Luke 18.1), Face

your abuser alone (Matthew 18.15), Only God is good (Luke 18.19),

Marriage is only for one man and one woman (Matthew 19.5), Divorce is

bad (Matthew 19.9), Believe without evidence (John 20.29), The world is

evil (1 John 5.19), Many are called but few are chosen (Matthew 22.14),

etc.

So Luther was correct drawing his amazing conclusion: "Since

God is a just judge, we must love and laud his justice and rejoice in

God even when he miserably destroys the wicked in body and soul, for in

all this his lofty and unspeakable justice shines forth. Thus even hell

is no less full of good, the supreme good, than is heaven. The justice

of God is God himself and God is the highest good. Therefore, even as

his mercy, so must his justice or judgment be loved, praised, and

glorified above all things" (LW 42:156).

13. Only Jesus Knows His

Own. The fact that only Christians go to heaven doesn't mean we know who they are. So Christians can't declare who's in and who's

out. Christ will make that judgment in the end (John 5.22). Jesus knows

his own and they know him (John 10.27). Until the end the weeds grow up

with the wheat and who's whom will not be settled until the end (Matthew

13.41-43). None of us can perceive that intimate relationship between

Christ and redeemed sinners (1 Corinthians 2.11-12).

For a while we think we might know them by the fruits of their

lives (Matthew 7.16). But things change. People drift away from

salvation (Hebrews 2.1). Others come back into it (Luke 15.17). Only God

sees into our hearts and knows our final disposition (1 Samuel 16.7;

Matthew 15.8). He is the final judge – not us.

Many haven't been able to endure this uncertainty about each

other. So schemes have been devise. One of the most famous was that

"good works" were "indispensable as a sign of

election" [Max Weber, The

Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, trans. Talcott

Parsons (1920, 1958) p. 115]. So people worked hard in order to prosper

and thereby prove their salvation – which of course was supposedly

granted freely to them through Christ Jesus. But because this scheme

jumped-the-gun and usurped Christ's place as judge, it was a failure

even though many relied on it anyway – and still do.

14. Making Faith Possible.

Why does God make it so difficult for us to believe? Why are we expected

to believe that so many are damned to hell? Doesn't damnation destroy

faith? No. It's actually the opposite.

If

God made good moral and intellectual sense he would be easily known and

understood. No risk would be required to believe in him – no venturing

out into what is unseen and only "hoped for" (Hebrews 11.1).

But faith requires such a risk. So God’s appearances upset us to test

us. Can we believe? His love looks like hate (Matthew 15.26-28). His

wisdom looks foolish and his power puny (1 Corinthians 1.23-25). In this

way he makes "room for faith." He creates a risk. Then we can

"believe him merciful when he saves so few." After all,

"if I could comprehend how... God can be merciful and just who

displays so much wrath and iniquity, there would be no need of

faith" (LW 33:62-63).

15. Untying the Knots.

Christians value simple explanations and straightforward statements (Galatains

2.14; 1 Corinthians 14.8; 2 Corinthians 4.2; Ephesians 4.14; 2 Peter

1.20, 3.16). We think beating-around-the-bush is bad. So why is this

essay on heaven and hell so involved? Couldn't it have been shorter and

simpler? I think not.

Our situation is like that of the

Cambridge

University

philosopher, Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951). He thought philosophy should be simple – all the while knowing that it simply

couldn't be. So he concluded: "Why is philosophy so complicated? It

ought, after all, to be completely

simple. – Philosophy unties the knots in our thinking, which we have

tangled up in an absurd way; but to do that, it must make movements

which are just as complicated as the knots.... The complexity of

philosophy is not in its matter, but in our tangled understanding"

[Philosophical Remarks (1964,

1975) p. 52].

If it were not for all our knotty confusions, we could have

simply sung these verses of Luther's hymn on Christ [Lutheran

Book of Worship (1978) No. 79] and left it at that:

To

his disciples spoke the Lord,

"Go

out to ev'ry nation,

And

bring to them the living Word

And

this my invitation:

Let

ev'ryone abandon sin

And

come in true contrition

To

be baptized, and thereby win

Full

pardon and remission,

And

heav'nly bliss inherit."

But

woe to those who cast aside

This

grace so freely given;

They

shall in sin and shame abide

And

to despair be driven.

For

born in sin, their works must fail,

Their

striving saves them never;

Their

pious acts do not avail,

And

they are lost forever,

Eternal death their portion.

|