|

Sermon 16

Soar

Like a Falcon Jeremiah

1:8 January

28, 2007 Sisters and brothers in Christ, grace and peace to

you in the name of God the Father , Son (X)

and Holy Spirit. Amen. God

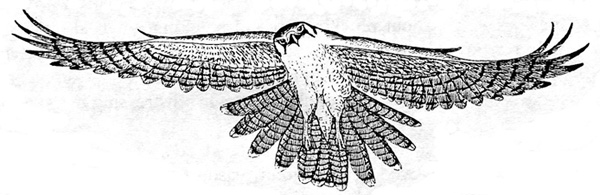

wants you to be strong and fly like a falcon – soaring high in

the sky. This image of the falcon is Luther’s. In his

commentary on Psalm 118 from 1530 he writes: “Let everyone

become a falcon and soar above distress” (Luther’s

Works 14:60). But

even though this image of the soaring falcon is Luther’s, the

idea of it is from the Bible. This note of fearlessness and

buoyancy is sounded throughout Holy Scriptures. And so God tells

the prophet Jeremiah: “Be not afraid, for I am with you to

deliver you” (Jeremiah 1:8). And to Joshua, the son of Nun,

God says the same: “Be strong and of good courage; be not

frightened, neither be dismayed” (Joshua 1:9). And Jesus tells

his disciples: “Fear not, little flock, for it is your

Father’s good pleasure to give you the kingdom” (Luke

12:32). And under threats from the devil himself, St. Peter

writes: “Resist him, firm in your faith” (1 Peter 5:9)! Jeremiah’s

Fears

Now why does God admonish us so? Why does he tell

Jeremiah, for instance, to quit being afraid? What was the

mighty Jeremiah afraid of in the first place? He was favored by

God before he was even born (Jeremiah 1:5). God had elected him

to be one of his greatest prophets ever. So surely he was safe

and secure – protected by God himself. Why then was he told

not to fear? Well,

quite simply, because he was afraid – contrary to what we’ve

imagined. This protected one of God was actually frightened too.

And this was because God had sent him to speak out against

nations and kingdoms. And he gave him hard words to speak –

words about plucking up and breaking down, destroying and

overthrowing (Jeremiah 1:10). And even though God had promised

to protect him, Jeremiah was still afraid – supposing some

sort of attack was inevitable, given his distressing message. Being

Yelled At

So Jeremiah believed he had good reason to be afraid.

Spouting off those four verbs of destruction would surely enrage

the people he was sent to warn. They would yell back at him! And

who likes that? They might even “grind their teeth” at him,

as others generations later would do against Stephen (Acts

7:54). In the face of such anger, it’s indeed natural to be

frightened.

And the anger also is predictable. For God’s words

offend us (Isaiah 30:9-11; Matthew 11:6). This is because these

words of liberation have restraints built into them. They cut

off as well as comfort. They include the Law with the Gospel

(Jeremiah 1:10; Isaiah 45:7; John 12:25; Romans 6:4). And

so God’s words go against the grain, or contra

naturam, as the old Latin Bible has it (Romans 11:24). They

attack our sense of self-worth (Luke 17:10) and inflated

self-importance. This is because “God abhors the confidence we

have [in] ourselves,” and demands that we be “humbled to the

utmost” (LW 3:4,

348). Because

these psychological constructs are so shaky from the start,

having been built on mere sand, when they teeter, even in the

slightest, we panic. And so we quickly dig-in and erupt in anger

to scare off the assailing Word and its messengers. “How dare

you!” we cry. “Let us burst their bonds asunder, and cast

their cords from us” (Psalm 2:3). The great poet, William

Blake (1757-1827), gave this indignation a classic rendition [Blake:

Complete Writings, ed. G. Keynes

( And

Priests in black gowns were

walking their rounds, And

binding with briars my

joys and desires. Being

Lonely

But Jeremiah had even more to fear than all this

anger and yelling. Because he brought such hard words from God,

his flock itself was set-up to go against him. They could turn

their backs on him, isolate and ignore him. They could throw him

into the dungeon of loneliness and shame. With their rejection

they could petrify him. Such

unpopularity is a hazard for God’s teachers and disseminators

of his holy Word. Whenever that Word is advanced, loneliness and

isolation follow quickly. So it’s right to say that “a

confessional Lutheran often becomes a ‘lonely Lutheran’”

[Robert D. Preus, “Dr. Herman A. Preus: In Memoriam,” Logia

4 (Reformation 1995) p. 57]. For with Luther we are driven to

say that the “world is below me, and heaven is above me. I

hover between the life of the world and eternal life, lonely in

the faith” (LW 14:181). This

is exactly what God’s hard words do to us. It’s the cost we

pay for witnessing to them. “I sat alone,” Jeremiah says,

“because your hand, O God, was upon me” (Jeremiah 15:17). We

fear nothing more than this sitting alone. Being unpopular seems

to be a fate worst than death. And so we’ll do almost anything

to rid ourselves of it. But against this fear of unpopularity,

God tells us to dig in. Be courageous and tough, he says.

Don’t be simpering. Being

Snookered

But that’s not the end of it either. Our fear

carries us still further. And we find ourselves fearing the

sophisticated. We fear those who, with kindness and composure,

criticize our faith in God. We fear we’ll cave in to what they

say. We fear we’ll give up on the Word of God. We fear we’ll

be talked out of pressing God’s hard words on sinners. We fear

we’ll be seduced into unbelief. Ever

since the snake in the Garden of Eden talked Eve out of

following God (Genesis 3:1-6; 1 Timothy 2:14), we have feared

those who question us. We fear being lead astray by their

interrogations. We fear being snookered. And so we crawl into a

hole and won’t argue with those who want to debate

Christianity with us. We cower before the prospect of

contestation (contra

Jude 1:3). We lose our nerve in the heat of disputation. Going

Against Timidity

But this is not as it should be. Losing our nerve

like this is based on mixed-up thinking. We are supposed to fear

God rather than people. In fact our fear of God itself is

supposed to see to it that we do this. So when you fear God

you’re not “merely to fall upon your knees” before him,

but you’re also to fear “no one” except him alone (LW 51:139). For fearing God is to change our lives! So

God won’t settle for our lack of nerve. He barges in and

fights for us – against us and our fears. 2 Timothy 1:7 says

that God replaces our timidity with “a spirit of power and

love and self-control.” Ephesians 3:12 says that this spirit

is what gives us our “boldness.” So we’re not to be done

in by our distress, agony, fear and suffering. Therefore when

darkness descends, do

not sit by yourself or lie on a couch, hanging and shaking your

head…. Do not… brood on your wretchedness, suffering, and

misery. Say to yourself: “Come on, you lazy bum [du

fauler schelm]; down on your knees, and lift your eyes and

hands toward heaven!” Read a pslam or the Our Father, call on

God, and tearfully lay your troubles before Him. Mourn and

pray…. God wills that you lay your troubles before Him…. He

wants you to grow strong in Him…. Otherwise men are mere

babblers [eitel plauderer]

(LW 14:61). In

the book of Acts, those preaching in the early church were

filled with just this sort of boldness. They didn’t succumb to

their misery. They weren’t fauler schelm and eitel

plauderer. So neither should we be now. A prime example of

this boldness is Christ Our Torch Now the Holy Spirit is still at work to make us

“defiant and courageous,” like But

if they “tread on Christ or on His Word,” then we must shift

gears and become “stubborn and impetuous hotheads,” glad to

be called “stiff-necked…. and headstrong asses” (LW

23:330). This is because true disciples of Jesus are “bold and

reckless” (LW

23:399). For when Christ is under attack we must not yield “a

hairbreadth to anyone” (LW

26:99, 44:93). Christ is Our Honor But how are we to manage this? How can we be so

strict? How can we tow the line? Now we can proceed

methodically, but sooner than we think, we fail. We can get off

on the right foot, but before we know it, we fall flat. So we

need something more if we’re going to advance at all. And

since we fail on our own, we need help from outside ourselves.

We need power from beyond us. Luke

4:32 says that Jesus spoke with authority. The old Latin Bible

translates this as in

potestate. Now that’s exactly what we need – power from

beyond ourselves. In

potestate! But how does Jesus manage that? Well, his power

for us is there in his obedience to God. As unlikely as that may

sound, that’s precisely where his power for us resides. When

faced with the worst predicament, he displays his incredible

will and personal force. When faced with a gruesome death, he

does not back down. Instead, he is “obedient unto death, even

death on a cross” (Philippians 2:8). In

his crucifixion he drains sin of its power over us. This is

what’s so powerful about his dying. He does this by having all

the sins of the world nailed into his body (1 Peter 2:24). This,

of course, takes great internal fortitude. And in this dying we

see the very power of God for us (1 Corinthians 1:24). For he

could have aborted his crucifixion. He could have come down from

the cross before he died. Three times the scoffers ordered him

down from the cross. “Save yourself,” they jeered at him as

he was dying on the cross (Luke 23:35-39). But Jesus holds firm

– refusing to flee from The Last Temptation of Christ Nikos Kazantzakis calls these taunts and jeers

against Jesus his last temptation – coming from the devil who

is finally striking him at the most vulnerable time (Luke 4:13).

In his novel he has the devil lure Jesus down from the cross

with these words: “Great joys await you… God left me free to

allow you to taste all the pleasures you ever secretly longed

for. Beloved, the earth is good – you’ll see. Wine,

laughter, the lips of a woman, the gambols of your first son on

your knees – all are good” [The Last Temptation

of Christ (1960) p. 446]. But Jesus doesn’t budge. His face is set

like flint to go to his death in In

Christ’s death he frees all who believe in him from their

guilt. This forgiveness of sins is our freedom. And in this

freedom we have the power we need to walk fearlessly. Now his

potency becomes our potency. Because of Christ we no longer

“need praise and honor among men.” Now he is “our Honor

and Glory” (LW 13:354)! Having these come from Christ, which are outside of

ourselves [extra nos],

they make us strong and “mettlesome” [animosos]

[The Book of Concord,

ed. T. Tappert (1580, 1959) p. 553]. This is because when the

source is outside of us and in Christ, then our discipleship is

based on the “denial of ourselves,” which draws us close to

him and to his power (Luke 9:23). So when the guilt and shame

that we have for our rebellion and disobedience weighs us down,

fear not. Though your hearts condemn you, “God is greater”

(1 John 3:20; James 2:13). Our Bag of Guilt Such dependence does not weaken us. It instead

miraculously enable us to do far more than we would ever think.

We find ourselves wonderfully going beyond our own capacities.

Even so we take no credit for any of this, but give all the

glory to God from whom it all comes in the first place (1

Corinthians 10:31). But

our unresolved guilt can still block all of this from happening.

Supposing that guilt isn’t a serious problem underestimates

our own weakness. For our unresolved guilt deeply damages us.

Robert Bly calls it a heavy black bag that we drag along behind

us wherever we go. The result of this is that the “bigger the

bag, the less the energy” [A

Little Book on the Human Shadow, ed. W. Booth (1988) p. 25].

Dragging this bag around with us, then, drags us down, draining

us of vital energy (contra

John 1:12-13). It robs us of the promised “abundant” life in

Christ (John 10:10). So

the forgiveness of sins isn’t at all puny. It’s rather quite

massive and filled with delight. It’s true that it requires us

to repent and muck around in our shame for a while (1 John 1:9),

but it doesn’t end there. It ends instead with absolution and

new life through the forgiveness of sins (Romans 6:4). So

there’s no need to “invent a special absolution for

yourself…. God does not want us to go astray in our own

self-chosen works or speculation” (LW

6:128). Only God’s forgiveness can free us (John 8:34-36). In

this freedom we acquire the “pitch of peace and poise” we

need to rise above our distress and suffering and fear (LW

44:77). Oscillating & Fragmented Even

though this divine absolution gives us power to “disdain”

all misery and shame, and sets us “against all power,”

thereby turning us into knights and heroes (LW

24:21), we still, even so, aren’t perfect (Philippians 3:12).

And we won’t be until we reach heaven after we die. Our life

with God now remains a “militant piety,” and not one of

triumph (Kierkegaard’s

Writings 22:130).

In our imperfection we experience oscillation and

fragmentation [Paul Tillich, Systematic Theology, 3 vols (1951-1963) 3:42, 140]. They mark our

life with God. First, then, our devotion to God oscillates. That

means some days we’re closer to God than others are. We have

our ups and downs. Sin, now and then, has its way with us –

like it did with David, Job, Jonah and Peter. And so we too must

say, “I believe, help my unbelief” (Mark 9:24).

In addition, even our good days are fragmented, fractured

and marred. That’s are second mark of imperfection. For when

we’re praying as we should, we often lack the required

humility, tenacity and clarity (Matthew 6:7; Romans 8:26; Luke

18:1, 11-12). And when we’re helping others, we still think

too much of ourselves (Luke 10:40). And when we have the right

plan in mind, we often fail to follow through (Romans 7:22-23;

Matthew 21:30).

What this means is that with all of our acquired

spiritual power and strength, we must never trust in ourselves

(Luke 18:9). We must recognize instead that we can do nothing

without God (2 Corinthians 3:4-5; John 15:5; Ephesians 2:8-9). Food Indeed So

rejoice in Christ and the mercy he brings us. Thank God for his

goodness in sending us his Son to save us. And receive him this

day in the Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper. Come to the Altar

of the Lord and bow down. Know that when you eat of the bread

and drink from the cup, Christ is truly there to be physically

received. He is “in, with, and under” the bread and the

wine, consecrated by the very words of our Lord Jesus Christ (BC,

p. 575). When you receive him, he promises to “abide” in you

that you might “abide” in him and be enriched by his

communion with you (John 6:56).

So this sacrament is for nourishment – therefore we

call it “food indeed” (John 6:55). It nourishes our faith

that it may “increase,” just as we would want (Luke 17:5).

For when you receive it and hear the Lord’s words that his

body and blood have been given “for you” (1 Corinthians

11:24), you know you haven’t been skipped over because of your

sin and unrighteousness. This reassurance is just what enhances

our faith in Christ. No wonder these two words, “for you,”

are the “chief thing” in this “most venerable sacrament”

(BC, pp. 352, 577). So

eat and then soar like a falcon! Love Rejoices in the Good But

faith without works is dead (James 2:26), and so we will leave

worship today with good works on our mind. And what good work

shall we do? God expects us to love because he first loved us (1

John 4:19). So let us rededicate ourselves to being loving

people. And

what will this entail? 1 Corinthians 13:7 famously says that

true love “bears all things.” This means that our love is

resilient and is not frighten off by bad behavior. When the

people we love show no gratitude for our caring, we just keep on

loving, even in this bad weather. So when your mother or father,

children, husband or wife, neighbors or fellow workers hurt your

feelings, keep on loving anyway. For love doesn’t require

sunny days to shine, it rather clears the clouds away on it’s

own. That’s what love does. But

true love still does even more than that. It also refuses to

rejoice in the wrong (1 Corinthians 13:6). So don’t you

rejoice in the wrong done by the people you love. Help your

friend, by all means, if she comes home drunk and sick to her

stomach. Even clean up the mess! But don’t tell her you like

seeing her incapacitated. No! For love doesn’t rejoice in

wrongdoing. Rather show kindness and then bring corrections and

suggestions to bear – and even admonitions and rebukes, if

need be (Luke 17:3; Titus 2:15). Then

call on God to bless you, that you might love with kindness and

correction as you ought (see Thomas C. Oden, Corrective

Love, 1995). May he grant you wisdom (Hebrews 5:12-14; Galatians

6:7; 1 Thessalonians 5:21; 1 John 4:1). And may he also grant

you compassion so that your love does no harm – harm caused by

rejoicing in the wrong (Romans 13:10). Amen. (printed as preached but with some changes) |