December 2019

|

|

|

|

|

What is Pleasing to God

I

really like the positive and helpful message on the back of our

offering envelopes.

It says: “A spirit of gratitude and generosity.”

These are fine and worthy attributes that we need to embrace in

order to become successful stewards so that we are doing what is

pleasing to God.

I

also love this prayer from the

Lutheran Book of Worship

that we pray together after the gifts of our tithes have been

presented to the Lord.

We pray:

“Merciful Father, we offer with joy and thanksgiving what you

have first given us, ourselves, our time and our possessions,

signs of your gracious love.

Receive them for the sake of him who offered himself for

us, Jesus Christ our Lord.”

This is a powerful prayer that we need to hear frequently in

order to be reminded of what the Lord God has done for us.

He loves us even though we are sinners and fall short of

the glory of God. May God bless you in your giving.

─Holly Petersen,

Church Council |

|

|

|

Exciting News!

For many

years the West Seattle Food Bank (WSFB) and the West Seattle

Helpline (WSH) have been strong partners.

Beginning in early 2019, WSH and WSFB came together to

actively explore ways to better serve the West Seattle

community. These

discussions led the Executive Directors and the boards of

directors of each agency to the decision to merge the services

into one organization.

In February 2020, the two boards will establish a new individual

board for the merged organization.

The combining of the mission will streamline neighbor’s

access to significant programs and services, while bringing two

strong organizations together to become stronger in offering the

community a more robust array of assistance.

Congratulations! |

Secular Pastoral Qualities

The Rev. Ronald F. Marshall

December 2019

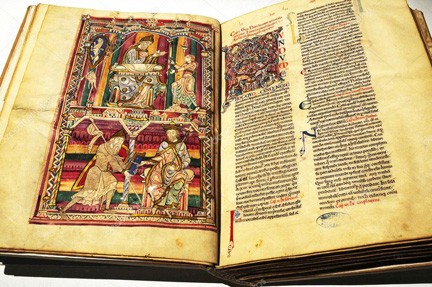

MARTIN

LUTHER ARGUED THAT ABOVE ALL PASTORS

must be faithful to the Lord Jesus – for “faithfulness is sought

and demanded” of them (Luther’s

Works 75:121). That alone, however, will not keep them in

the public ministry. Every year many ministers drop out of the

ministry at a high rate because they’re not suited for it (Faithful

and Fractured: Responding to the Clergy Health Crisis, 2018;

Brooks R. Faulkner,

Burnout in Ministry, 1981). What could change that? What

simple, secular, human traits would help pastors stay in the

ministry?

Ideas. If

you aren’t intellectual – having no interest in ideas or

abstractions – then you aren’t suited to be a pastor. The Bible,

after all, has over a thousand pages of ideas in it! So laboring

over such things as the different nuances between justification

and sanctification should be fascinating and invigorating. If

not, stay out of the ministry. Preachers, after all, “work in

words because God condescends to human speech” (Will Willimon,

Accidental Preacher,

2019, p. 154). There’s no escaping this, since “the Word, the

Word, the Word,… everything [in Christianity] depends on the

Word” (LW 40:212,

214). A “love of words,” then, wouldn’t be inordinate for

pastors (K. M. E. Murray,

Caught in a Web of Words, 1977, p. 333). Before God’s Words

preachers should stand “as wan and wild, as if they had seen a

spirit” (A. Habegger, My

Wars are Laid Away in Books, 2002, p. 312).

Bold.

Pastors are expected to stand up in front of people and talk in

public with confidence. If you’re too shy to do that, and it

makes you sick even to try, go into something else. Jonah,

remember, had the nerve to address the great city of Nineveh –

and tell them God was going to kill them (Jonah 3:4) – an

“extraordinary” feat (LW

19:49). And Saint Peter preached to thousands of Jews telling

them that they were condemned for killing Jesus (Acts 2:14–36).

Boldness has long marked the ministry (Acts 4:13, 29, 31, 9:27,

29, 13:46, 14:3, 18:26, 19:8, 2 Corinthians 3:12, Philippians

1:14, Ephesians 3:12, 6:19).

Multiplicity.

Pastors do many things at once and are always being interrupted.

If that drives you crazy – being pulled in opposite directions –

then don’t be a pastor. But if you find that whirl of

contradictory demands enriching and inspiring, then being a

pastor could be the ticket – the taking up of “all things” (1

Corinthians 9:22). It’s humbling to know that the ministry

doesn’t care about you focusing on one thing (Luke 10:42). The

fact that “God is not a God of confusion” (1 Corinthians 14:33),

doesn’t mean your life won’t be.

Sensitivities.

If your feelings are easily hurt, stay out of the ministry (I.

Sand & E. Svanholmer,

Highly Sensitive People in an Insensitive World, 2016).

Pastors need to have thick skin. That doesn’t mean, however,

that they ignore all the troubles around them. It’s just that

they don’t take any of it personally – even when they are being

attacked individually. They instead work to stay on topic. This

means they have strong emotional intelligence – and so they

don’t storm out of rooms and slam doors (D. Goleman,

Emotional Intelligence,

2005).

Curiosity.

If you don’t find people fascinating, the ministry will bore

you. Learning about the people you work with should be exciting

to you. That doesn’t mean that you’ll have to like everyone. No,

the nasty you simply will “avoid” (Romans 16:17). Still, pastors

should be people-persons. Loners have no place in the ministry –

all it will do is suffocate them. Pastor are interested in

people because their stories show “how this man or that woman

whose public life interests us has negotiated the problem of

self-awareness and has broken the internalized code a culture

supplies about how life should be experienced” (J. K. Conway,

When Memory Speaks,

1998, p. 17).

Conflict.

The ministry is full of conflict, chaos and confusion (Kenneth

C. Haugk, Antagonists in

the Church, 1988). If this buzzing mess doesn’t intrigue you

– find other work. Pastors have to want to enter into the fray –

and stay there for the long haul like “bulls” (LW

10:320). One pastor reports: “My days… were typified by

squabbling, disappointment followed by undeniable failure,

fornication between an alleged soprano and a bogus baritone,

[and a couple] duking it out in the parking lot before a

wedding” (Accidental

Preacher, p. 81). And another concludes: “[Regarding the

pastor, he is] either coming out of a storm, in a storm, or

heading for a storm” (H. Beecher Hicks, Jr.,

Preaching Through a Storm,

1987, p. 18). Ministry is a bumpy ride.

Writing.

Writing down your ideas is important for pastors. So if you

suffer from writers’ block, and it takes you forever to write

out anything, you’ll quickly burn out in the ministry. Saint

Paul is our example. He couldn’t have done his ministry without

writing down his intricate letters – unlike Jesus who wrote

nothing at all, except twice with his finger in the dirt (John

8:6–8). Nevertheless, Saint Paul’s letters “are the mountain the

teaching of the carpenter of Nazareth congealed into,” which no

one has been able to “scale” (Poems

of R. S. Thomas, 1985, p. 162). They, indeed, are very

challenging (2 Peter 3:16). So deft and challenging writing is

also part of the ministry. Saint Paul therefore shows us that

there’s a place for such complex letters and the like – to serve

as analyses of, and elaborations on, the simplicity of faith and

action. The same is expected of all pastors.

The Last American Church

The Rev. Ronald F. Marshall

First Lutheran Church of West Seattle

December 2019

Those who like our church tell me that it is

the only one like it left in America. When I hear that I think

of Larry McMurty’s famous novel,

The Last Picture Show

(1966) – which Peter Bogdanovich made into an award winning

movie in 1971 by the same title. But what makes our church the

last of its kind? I think it is because of these eight things

that we’re simultaneously working on constantly –

unlike all other churches.

The Acerbic Word God’s word is tough – and we don’t soften it.

Martin Luther said it’s “Christian severity” – and is “harsh” to

our hearing (asperam

veritatem) (Luther’s

Works 26:118, 11:58). We’re constantly striving for the Word

that smashes us with a hammer, burns us up with fire, and cuts

us into pieces with a two-edged sword (Jeremiah 23:29, Hebrews

4:12). We don’t try to run away from the Law that sends “the

lightning of divine wrath,” nor from the Gospel that

“suppresses” all the other salvations “of the flesh” (LW

26:310, 14:335). We need this dying (Galatians 2:20).

The Historic Liturgy The ancient ordo of worship is best. So we

don’t experiment. Neither do we entertain when we worship

Almighty God (The Book of

Concord, ed. T. Tappert, p, 378). We keep the old forms of

ascending and descending (LW

36:56). We stand for the “true Christian mass according to the…

institution of Christ” (LW

38:208). The Lutheran

Book of Worship (1978) does this best. On how the

ELW (2006) fails, see

R. F. Marshall, “Evangelical

Lutheran Worship and Universalism,”

CrossAccent 2007.

Moral Convictions Moral experiments don’t help. Ancient codes

hold wisdom (see

Connecting Virtues, ed. M. Croce & M. Vaccarezza, Wiley,

2018). Ethics designed to preserve favorable views of ourselves

are wrong (as in K. Appiah,

The Ethics of Identity,

Princeton, 2005). Virtue exceeds identity.

Children as Apprentices

Children’s sermons and youth Sundays are wrong. The young are in

training to become adult Christians. We don’t want a Christian

version of William Golding’s novel,

Lord of the Flies

(1954). We follow Søren

Kierkegaard (1813–55): “Christianity as it is found in the New

Testament,… is impossible for children [for it holds to] a good

which is identified by its hurting, a deliverance which is

identified by its making me unhappy, a grace which is identified

by suffering” (Journals,

ed. Hongs, §4:5007).

So we follow the critique of childish Christianity (1

Corinthians 13:11) in Thomas E. Bergler,

The Juvinalization of

American Christianity (Eerdmans, 2012). All of this is a

massive undertaking because it includes Luther’s austere view

that we need to train our children to “neither fear death nor

love this life” (LW

44:85).

Complex Music Church music is to challenge aesthetically

and spiritually. So Luther admonishes: “Takes special care to

shun perverted minds who prostitute this lovely gift of nature

and of art with their erotic ranting; and be quite assured that

none but the devil goads them on to defy their very nature which

would and should praise God its Maker with this gift [of music],

so that these bastards purloin the gift of God and use it to

worship the foe of God” (LW

53:324). So the gold standard is Luther’s “A Mighty Fortress is

Our God” (1528) – but new hymns like, “We Had to Have Him Put

Away” (2014), also have a place in the church (listen to it at

flcws.org). New music isn’t as important as what kind of new

music it is.

Helping the Poor Rather than seeking the favor of the wealthy

and powerful, we strive to “associate with the lowly” (Romans

12:16). In most cases the lowly are the homeless and the hungry

– but the sexually abused and politically oppressed cannot be

left out (Luke 10:37).

Beauty In our architecture, gardens, vestments and

paraments, we avoid mismatching materials, colors and shapes;

poor construction; and using shoddy materials (Monroe C.

Beardsley, Aesthetics,

1958, pp. 527–530). And we also favor the historic symbols of

the church. We must never forget that God loves beauty (Psalm

27:4, Romans 10:15).

Small Quantitatively

Martin Luther is right that “size does not make the church” –

and so “what matters… is not becoming great, but becoming small”

(LW 2:101, 67:325).

The church, then, should not conform to worldly majorities

(Romans 12:2) – it’s a “little [μικρος]

flock” (Luke 12:32): “The church in the next several decades is

going to be a smaller, leaner, tougher company. I am convinced

that the way for the church now is to accept the shrinkage, to

penetrate the meaning and the threat of the prevailing

secularity, and to tighten its mind around the task given to the

critical cadre” (Joseph A. Sittler,

Grace Notes and Other

Fragments, 1981, p. 99).

|

|

Man is that

thing of sad renown Which moved

a deity to come down And save

him. Lay not too much stress Upon the

carnal manliness: The

Christliness is better – higher; And Francis

owned it, the first friar.

[The Poems of Herman Melville,

ed. D. Robillard, 2000, pp.

246–47.]

|

Reason’s Failure

Offending Professor Burtness

By Pastor Marshall

This

altercation taught me how little rationality held sway when I

was at the seminary – in spite of its vaulted status. Professor

James H. Burtness (1928–2006) was a prestigious professor at the

seminary, a prized Bonhoeffer scholar, with a doctoral degree

from Princeton, and very popular among the students. I wrote a

term paper (November 25, 1974) for his seminar on Bonhoeffer

which was critical of Bonhoeffer’s famous claim that only a

suffering God can help (DBW

8:479). He didn’t much like the paper because he was a devotee

of Bonhoeffer, and particularly that passage (1906–45) – even

though he couldn’t fault my paper for any research errors. I

showed my paper to another seminary professor and he thought it

was good enough for me to present at the regional meeting of the

American Academy of Religion – the leading guild on religious

studies. I accepted the invitation (April 4, 1975). But when

Burtness heard of this, he was enraged and wrote me this note

(April 6, 1975), without ever talking to me in person: “It did

seem strange to me that you wouldn’t consider any of my comments

on your paper worth following up prior to facing that audience.

Even if you didn’t think my opinion worth checking, it would

have been a nice little courtesy…. If you can help it, you don’t

want to give your professors the idea that you have nothing to

learn from them… You did hurt me [and you might hurt others too]

with similar sensitivities.” This was the first such case of

irrationality in my life in higher education, but not the last –

lamentably. |

Sunday, December 15

from 1:00pm to 4:00pm In a week or

so we will be gathering in the “transformed” Parish Hall to

celebrate Saint Nicholas Day by hosting an event to commemorate

the generous spirit of Saint Nicholas.

His many acts of charity

are legendary. All

proceeds from this Faire will be donated to the West Seattle

Food Bank and the West Seattle Helpline. This year we

will be having 3 events at the Faire:

P

Basket Auction

P Live Auction

P

Raffle

Basket Auction:

Here’s a sampling of the gift

baskets that will be available to bid on…..

Children’s Books

Air Fryer

Children’s Science Gear

Beer & Wine

Gardening

Baked Goods

Seahawks Gear

Olive Oil/Vinegar

Framed Photo’s

Kitchen Gadgets

Tools

U of W Gear

Holiday Items

Barware

Baking Tools

Storage Containers

Art Supplies

Tea & Coffee Items

ETC!

ETC!!

ETC!!!

Plus gift certificates to many

local restaurants and businesses like Elliott Bay Pub & Brewery,

Husky Deli, Trader Joe’s, West Seattle Nursery, Junction

Hardware, Spiros, Amazon, Spuds, Admiral Theater, Pegasus Pizza,

Staples –

ETC!,

ETC!!,

ETC!!!,

ETC!!!!

Live Auction:

There will be 2 items offered

at a live auction.

1.

One Night Stay at Leavenworth’s Abenblume Valued at $300, with

$100 gift card for Restaurant.

2.

May 15-17, 2020 Two Night Stay at Lake Chelan Area Wapato Lake

Waterfront Retreat (Maximum capacity 8 people).

Includes $100 Gift Card at Blueberry Hills Restaurant.

Total Value $600.

But the most important way to

support this event is to come and bring your family, friends and

neighbors, and do your Christmas shopping. |

|

||

Join us for the Four Sundays of

Advent

Sundays:

8:00 am Holy Eucharist, in the chapel

10:30 am Holy

Eucharist, in the nave

8:00

pm Compline, in the chapel

THE NATIVITY OF OUR LORD Celebrate with us the great Christmas feast of our Lord's

Nativity. May these days fill your prayers with thanksgiving and blessing.

Christmas Eve

Liturgy of

Lessons, Carols, & Holy Eucharist

11:00 pm Holy Eucharist, in the nave

Christmas Day

Festival

Liturgy & Holy Eucharist

10:30 am Holy Eucharist, in the nave

St. Stephen, Deacon and Martyr

11:45 am Holy Eucharist, in the chapel

St. John, Apostle and Evangelist:

Friday, December 27, 2019:

11:45 am Holy Eucharist, in the chapel

The Holy Innocents, Martyrs:

Saturday, December 28, 2019

11:45 am Holy Eucharist, in the chapel

To end the 12

days of Christmas be sure to join us on –

11:45 am Holy Eucharist, in the chapel |

|

ANNOUNCEMENTS:

DECORATING SIGN UP LIST:

Please sign up if you are able to help with church

decorating this year.

The sign up sheet will be posted in the hallway by room

C.

PASTOR MARSHALL’s next four week class on

the Koran starts on Thursday, January 9th.

Call the office to register for the class.

FOOD BANK COLLECTION suggested donation for

December is holiday foods.

And, don’t forget to bring a couple of cans of food to the

Saint Nicholas Faire!

SACRAMENT OF PENANCE:

Saturday., December 21st, 3-5 pm.

CHRISTMAS CAROLING PARTY:

Thursday, December 26th, meet at Christo’s on Alki at 5:00 pm

for a no host meal.

Then go caroling to shut-ins in the congregation.

Everyone is welcome to come along.

Please sign up on the list that is posted in the lounge.

2020 FLOWER CHART:

The new chart for 2020 will be up at the end of the

month. Sign up early

for the best choice of dates.

JOHNSON CN:

Our thanks to Ben Johnson and Johnson CN for the

financial and technical support donated to the church office.

It is very much appreciated.

|

|

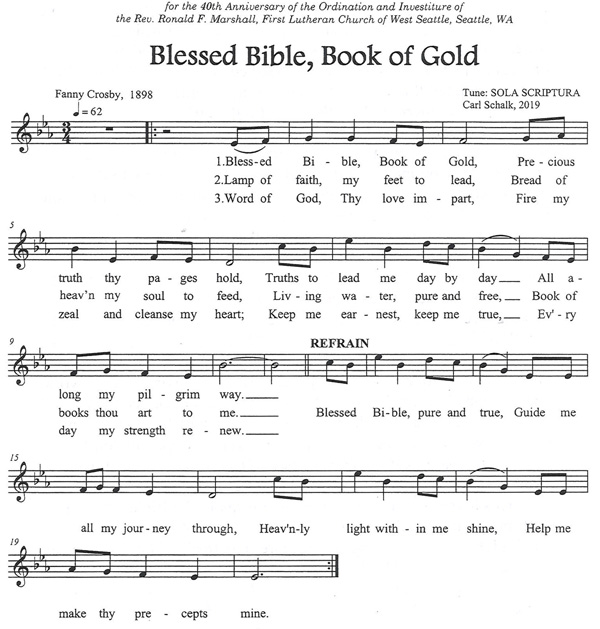

For You

In

celebration of the 40th Anniversary of my Ordination, I have a

gift for you – in thanks-giving to God for your support over the

years. I have collected my twelve one page sermons from this

year into a booklet called,

A Narrow Flood. Note

the sewn binding – courtesy of Puget Bindery, Kent, Washington.

–Pastor

Marshall |

|

|

Saint Editha’s Church, Tamworth, England

A Baptism Poem

Today we wounded you with the wound that heals.

Waters of chaos break over your head

and you are drowned in Christ. You bear his seal.

Only the one who raises up the dead

can bear us on that devastating flood

which saves us from ourselves and makes us whole.

We watch you coming through, our flesh and blood.

One little word shatters and kills the old.

Upon your brow and on your breast you bear

a mark that neither life nor death can change.

Your grandfather was called to put it there

with words that will forever make you strange

and alien in a world that is too grave

to risk undoing in this chaotic wave.

[from Gracia Grindal, “Baptism (For Karl Theodore),”

A Revelry of Harvest: New and Selected Poems,

Lincoln, Nebraska: Writer’s Showcase, 2002, p. 60 –

reprinted by permission.]

|

|

|

Remember in prayer before God those whom He has made your

brothers and sisters through baptism.

Louis & Holly Petersen, The Tuomi Family, Bob Baker, Sam & Nancy

Lawson, Pete Morrison, Eileen & Dave Nestoss, Bob & Barbara

Schorn, Aasha Sagmoen & Ajani Hammond, Connor Sagmoen, Kyra

Stromberg, Tabitha Anderson, Diana Walker, The Rev. Howard

Fosser, The Rev. Kristie Daniels, The Rev. Kari Reiten, The Rev.

Dave Monson, The Rev. Albin Fogelquist, The Rev. Chelsea Globe,

Sheila Feichtner, Antonio Ortez, Richard Uhler, Yuriko

Nishimura, Leslie & Mark Hicks, Eric Baxter, Deanne Heflin,

David Douglass, Owen & Noreen Marten, Jim & Bonnie Henningson,

Mary Ford, Nancy Wilson, Nell & Paul Sponheim, Mary Lou & Paul

Jensen, Rubina & Marcos Carmona, Rosita Moe, Mary Blom, Claudio

Johnson S, Bjorg Hestevold, Tatiana Ceaicovschi, Jim Thoren,

Trevor Schmitt, Cathy Conord and Karen Mulcahy.

Also, pray for unbelievers, the addicted, the sexually

abused and harassed.

Pray for the shut-ins that the light of Christ may give them

joy: Bob & Mona

Ayer, Bob & Barbara Schorn, Joan Olson, Doris Prescott, C. J.

Christian, Dorothy Ryder, Lillian Schneider, Crystal Tudor, Nora

Vanhala, Anelma Meeks, Martin Nygaard, Gregg & Jeannine Lingle.

Pray for our bishops Elizabeth Eaton and Shelley Bryan Wee, our

pastor Ronald Marshall, our choirmaster Dean Hard and our cantor

Andrew King, that they may be strengthened in faith, love and

the holy office to which they have been called.

Pray that God would give us hearts which find joy in service and

in celebration of Stewardship.

Pray that God would work within you to become a good

steward of your time, your talents and finances.

Pray to strengthen the Stewardship of our congregation in

these same ways.

Pray for the hungry, ignored, abused, and homeless this Advent &

Christmas. Pray for

the mercy of God for these people, and for all in Christ's

church to see and help those who are in distress.

Pray for our sister congregation:

El Camino de Emmaus in the Skagit Valley that God may

bless and strengthen their ministry.

Also, pray for our parish and it's ministry. |

|

Forgive me,

Almighty God, for camping on the periphery and living on the

border, and never facing the central sins of my life. Made for

truth, I am deceptive. Capable of deep caring, I’d rather be

cared for. Created to live with you, I’m too busy to pray.

Intended for the profound, I settle for the trivial. In your

mercy, draw me to the center, through faith in you. In the name

of Jesus I pray. Amen.

[For All the

Saints II:1262, altered] |

.jpg)