November 2021

|

Kierkegaard on Not Worrying

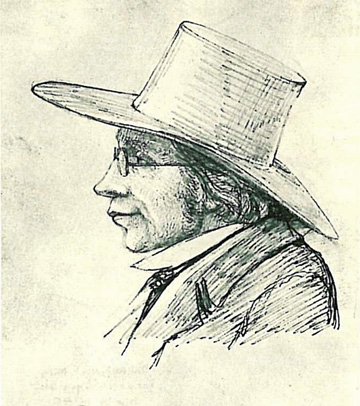

In 1847 Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) published in one little

book three discourses or studies on Matthew 6.26 about how God

feeds us in the way he feeds the birds. I think it’s worth

pondering repeatedly:

Be contented with being a human being, with being the

humbled one, the created being who can no more support

himself than create himself. But if a human being wants

to forget God and support himself, then we have worry

about making a living. It is certainly praise-worthy and

pleasing to God that a person sows and reaps and gathers

into barns, that he works in order to obtain food; but

if he wants to forget God and thinks he supports himself

by his labors, then he has worry about making a living.

If the wealthiest man who has ever lived forgets God and

thinks he supports himself, he has worry about making a

living. Let us not talk foolishly and narrow-mindedly by

saying that the wealthy man is free from worry about

making a living and the poor man is not. No, only that

person is free who is contented with being a human being

and thereby understands that the heavenly Father feeds

him – and this, of course, the poor can understand just

as well as the wealthy

(Kierkegaard’s

Writings

15:177).

So be sure to thank God for whatever you have, taking no credit

for any of it, and knowing that whatever it may be, it’s what

God thinks is best for you.

—Pastor

Marshall

(Reprint from

The Messenger

November 2010)

|

|

PRESIDENT'S REPORT...by

Cary Natiello

Dear friends of First Lutheran Church,

This will be my final president’s report to you before Nelly and

I start on our adventure and head south for the winter.

My thoughts and prayers have been with Pastor Marshall these

past few weeks. At

the time of writing this, he remains hospitalized and is still

waiting for test results so his providers can come up with

optimal treatment options.

Recently, Jane wrote to the Jonah Bible Study group…

Ron is still on the "sick-list" this week and asked me to

contact you again. I know he is looking forward to online

classes with you again SOON, but he is still hospitalized. The

last few days he has been walking the halls and working the

crowd! Some things never change...

He has been meeting so many Christians during his hospital stay

who are complete strangers and have offered him support. He

knows that God is watching over him.

Walking the halls, working the crowd, and meeting so many

Christians who are complete strangers….Doesn’t

that sound so much like Pastor Marshall!

God certainly works in mysterious ways.

Janine Douglass, current Vice-President, will assume the

president’s duties beginning November 10th, after the November

9th council meeting.

She has also agreed to be nominated for president for the

2022 – 2024 term. I

am thankful to Janine for her gracious willingness to jump in

and cover the balance of my president’s term.

Serving on the council since 2017 has been a blessing and honor

for me. After my

wife Cynthia passed away in 2016, I was so lost, and I felt no

longer with any purpose.

I prayed for guidance and my prayers were answered by you

all allowing me to serve at First Lutheran Church in a

meaningful and productive manner on the council.

Thank you all for your support.

Lastly, a special prayer for Pastor Marshall…

God’s peace be

with you all.

|

|

STEWARDSHIP

A Stewardship Sampling

Below are excerpts from previous stewardship articles and

sermons that I put together to share with you for this month’s

stewardship article:

·

Stewardship means using our talents to glorify God.

·

A beginning point in looking for ways to best be good stewards

is to listen in prayer and be open to God’s guidance.

·

Search the Bible for answers to stewardship.

Search your hearts for opportunities to grow in your

understanding and application of how we can each better commit

our talents and gifts to the life of the church.

·

We are the trustees of the time, talents, gifts, treasures and

the values of the community we all live in.

·

“As you, Lord, have lived for others, so may we for others

live.” LBW 364.

·

Even though our life is a little rocky right now, we are still

required to be responsible stewards of our commitments which

would include time, talents and money.

·

Politics aside, as Christians, we are called to be stewards of

the earth.

·

I am reminded of the parable of the talents where three workers

were given various amounts of talents to care for – two of them

used it to increase their value for the owner; the third one

buried it where it just got dirty and did not grow.

We are to use what he allotted to us in the best way

possible and for his glory.

·

In our congregation we...honor the beauty and majesty of our

church building as God’s holy house wherein we do far more than

meet together, but primarily behold the awesome splendor of

God’s presence.

·

Faith apart from works is dead. James 2:26

·

A generous person will prosper; whoever refreshes others will be

refreshed. Proverbs 11:25

Cary Natiello, Church

Council |

|

Saint Nicholas Faire

&

Auction

Wednesday through Monday, November 24-29th, 2021

6 pm to 9 pm

For the second

year the Saint Nicholas Faire & Auction will be a Virtual

Fundraiser sponsored by First Lutheran Church of West Seattle

with

all proceeds benefitting

the West Seattle Food Bank.

We continue to chair this event to honor the memory of Scott’s

grandmother Alfhild Schorn, who worked tirelessly during the

Depression to feed the hungry that showed up on her doorstep.

Our goal of $15,000 would surpass prior years and can be

obtained with your help. We

ask you to help in two ways.

First by purchasing items from the Saint Nicholas Faire &

Auction Amazon wish list

https://www.amazon.com/hz/wishlist/ls/37THT2NYXHT62/ref=nav_wishlist_lists_2?_encoding=UTF8&type=wishlist;

we then catalog the items and make them available on the Virtual

Auction site.

Secondly we ask you to attend and bid at the Auction on one or

all six days.

We understand that Thanksgiving weekend can be a busy time; but

we ask that you think about those who will benefit from the

proceeds. Cash

Donations can also be donated on the Auction site, or sent

directly to First Lutheran Church of West Seattle, clearly

marked for the Saint Nicholas Faire & Auction.

Once the Auction site is live we will share the link for you to

pass on to family & friends, the more bidders, the closer we

come to reaching our goal.

With your help we can meet or beat our goal of $15,000, and help

those in need within our neighborhood.

In Christ we can do all things.

-Scott & Valerie Schorn |

|

Misconstruing Miracles

By Ronald F. Marshall

In his high profile

Newsweek article, “Why I Don’t Believe in Miracles,”

Professor Philip Hefner of the Lutheran School of Theology at

Chicago since 1967 stumbles and falls.

In this article which was part of the cover story on miracles,

he argues against miracles and in favor of blessings.

Blessings he proposes are to be preferred over miracles

because they – unlike miracles – do not contravene the laws of

nature.1

Yet in the course of pursuing his startling thesis he is

incoherent, inconsistent and even blasphemous.

As a result he not only weakens his case but also

seriously misconstrues miracles.

Hefner’s article is incoherent because even though he favors

blessings because they – unlike miracles – do not violate the

laws of nature, he still goes on to say these blessings

themselves occur “unexpectedly.”

But how would he know that unless these blessings also

violated what David Hume famously called “the common course of

nature?”2

For them to be unexpected they would have to go against

the ordinary.

Hefner’s blessings would have to push against reality as it

usually goes if they were to manifest the unexpected.

So on Hefner’s own account, blessings would need – just

like miracles do – what Richard Purtill calls a “contrast idea”

in order to be coherent.3

If no expected pattern is violated, then it would be

incoherent for Hefner to say blessings occur “unexpectedly.”

So by insisting that blessings occur unexpectedly he

renders his argument incoherent.

Next his argument is inconsistent.

Hefner in part condemns miracles because they occur

unevenly – leaving many who suffer without the help they so

desperately long for.

This is because many prayers appear to go unanswered.

This uneven distribution he vilifies as “blasphemous”

because it gives God a bad name.

If God helps one he should help all.4

“That’s where the blasphemy comes in,” howls Hefner.

Due to the spotted, selective occurrence of miracles God

comes off looking less loving than he actually is.

Due to our belief in miracles God appears arbitrary and

cruel.

But blessings are no different – even on Hefner’s account!

They too occur sporadically.

Blessings are not uniformly distributed throughout

reality. Feast and

famine strike farmer and entrepreneur alike.

So throwing out miracles for blessings does nothing for

God’s image. “Even

though we cannot…understand why so much of human life involves

sorrow and evil,” Hefner insists we should still “be grateful

and render praise” for whatever blessings come our way.

But this is inconsistent.

It is special pleading.

If irregularity strikes down miracles, then it should –

if one were to be consistent – strike down blessings as well.

But Hefner abandons

consistency, falls on his own sword and unwittingly flays his

argument to pieces.

Finally

Hefner himself blasphemes when he says he has “no confidence”

that his prayers actually “change the course of nature.”

But as Lutherans we are to confess that our prayers are

“assuredly heard and granted."

Whoever denies this “grossly dishonors” God!5

Hefner goes where angels fear to tread all because of the

common experience of not getting what we pray for.

But there is a better way of handling that disappointment

than committing blasphemy.

Down through the generations Christians have learned to “be

exercised in prayer.”6

This means changing your mind about what you pray for.

Then what we want gives way to what God wants.

Longing and praying for one’s heart’s desires trails off

into affirming God’s will instead.

Indeed, “how could the prayer of the children of adoption

be centered on the gifts rather than the Giver?”7

So when we pray for the sick we should not pray for

healing alone. We

should also add that God’s will be done and that we learn to

accept whatever it is.

Our prayers must never go beyond the tax collector’s

humble prayer: God,

be merciful to me a sinner!” (Luke 18:12).

This is because in the end we are all beggars.

Wir sind alle

Bettler is our only motto.8

Thomas Fuller (1608-1661) catches this humility wonderfully well

in his prayer:

“Lord, teach me the art of patience whilst I am well, and give

me the use of it when I am sick.

In that day either lighten my burden or strengthen my

back. Make me, who

so often in my health have discovered my weakness presuming on

my own strength, to be strong in my sickness when I solely rely

on thy assistance.9

The impression Professor Hefner gives in his attack on

miracles is that this prayer would make him choke.

Because this humility is missing from Hefner’s account he

stumbles and falls the way he does.

If he had incorporated humility into prayer we would then

have been able to see how they are answered over and over again.

By missing this he also drains his account of the

following wisdom: “Do not be troubled if you do not immediately

receive from God what you ask him; for he desires to do

something even greater for you, while you cling to him in

prayer.”10

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Endnotes

______________________________________________________________________________________________

1Philip

Hefner, “Why I Don’t Believe in Miracles,”

Newsweek (May 1,

2000) 61.

2David

Hume, “Of Miracles” (1758),

In Defense of Miracles: A

Comprehensive Case for God’s Action in History, eds. R.

Douglas Geivett and Gary R. Habermas (Downers Grove: Inter

Varsity Press, 1997) 33.

3Richard

L. Purtill, “Defining Miracles,”

In Defense of Miracles,

63.

4So

much for Psalm 115:3 which says our “God is in the heavens; he

does whatever he pleases,” and Romans 9:18 which says “God has

mercy upon whomever he wills, and he hardens the heart of

whomever he wills.”

By excising this raw contingency from divine nature Professor

Hefner flattens out God and renders him languid.

All that this leaves us is a useless “prettified God”

[Gerhard O. Forde, On

Being a Theologian of the Cross, (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans,

1997) 85.]

5Martin

Luther, Large Catechism (1529), III.20, 21,

The Book of Concord,

eds. Robert Kolb and Timothy J. Wengert, (Minneapolis: Fortress,

2000) 443.

6Catechism

of the Catholic Church, Revised Edition, (London: Geoffrey

Chapman, 1999) 2737.

7Catechism

of the Catholic Church, 2740.

8These

last words of Luther’s translate: “We are all beggers.”

On this motto see James M. Kittelson,

Luther the Reformer: The

Story of the Man and His Career, (Minneapolis: Augsburg,

1986) 297.

9The

Oxford Book of Prayer, ed. George Appleton, (New York: Oxford,

1985), (437) 130.

10Catechism

of the Catholic Church, 2737.

dialog: A

Journal of Theology

Volume 39, Number 4 •

Winter 2000

______________________________________________________________________________________________

A Moratorium on Miracle-Talk?

______________________________________________________________________________________________

….The words of Psalm 115:3, “God is in the heavens, God does

whatever [he] pleases,” do not go down easily.

There are those who are moved by these words rather to

deny God than to bow down in worship.

This is the experiential and pastoral context in which talk

about miracles takes place today.

By referring to miracles, we assert our belief and our

hope that the God who sends afflictions upon us will also rescue

us. The article I

wrote in the May 1, 2000, issue of

Newsweek, to which

the Reverend Ronald Marshall responded in this journal (Winter

2000, vol. 39:4), elicited fifty letters.

Most were written by lay people and they expressed the

context I have just described – some of them very poignantly.

Six of these letters (5 by Lutherans, 4 by clergy) were

in the slashing mode that Marshall adopted; the rest revealed

the serious probing of men and women who are struggling on their

way, seeking help wherever they can find it.

….Some responses to my original article judged the quality of my

faith according to whether or not I accept miracles.

Some, like Marshall, suspect that I have no faith because

I question miracles.

Others took my skepticism as a sign that my faith was

strong and wholesome.

One letter published by

Newsweek (May 8,

2000) wrote that my “vision implies a God acting always and

everywhere through natural law rather than fitfully and

arbitrarily countermanding natural law.

A professor offering an argument of scientific and

theological sophistication in clear, elegant language –

now that’s miraculous!”

….There are those who express doubts about miracles to their

pastor, priest, or Christian friends, only to be met with the

kind of judgmental invective that Marshall hurled at me.

These people expressed gratitude for my article; it

actually seemed to strengthen their faith and perhaps even their

churchgoing.

When I think about miracle-talk, these experiential and pastoral

issues seem most important.

Frankly, in light of the ambiguities and

misunderstandings involved, I question the usefulness of the

idea of miracle.

More often than not, such talk is not a clear witness to the God

who rescues. I

suggest a moratorium on such talk.

What should we do in a period of moratorium?

Let us promote serious reflection and conversation in our

communities about how we see God at work in our lives and what

forms that work takes.

Let us be as honest as Scripture about our difficulties

and agonies when we reflect on God’s presence in our lives and

in our world. Let

us be specific about those things we want to give God thanks and

praise for: I

suggested in my article that we might use the term “blessing” to

speak of these things.

Let us speak candidly about what things about God

bewilder us and what things might prompt us to cry out with

Psalm 22: “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?”, as well

as the later verses of that psalm: “God heard when I cried out….

Posterity will serve God; future generations will be told and

proclaim God’s deliverance.”

The Reverend Marshall will probably not consider these comments

a worthy response to his piece.

However, I do not see much connection between my original

Newsweek article and

his response to it.

I encourage readers to retrieve my original article and draw

their own conclusions.

P.S. I will gladly

send copies of the article to readers who request it (fax:

773-256-0682; e-mail:

zcrs@lstc.edu).

Careful readers will note several mis-readings in

Marshall’s piece.

For example, I say that blessings are “often” unexpected, not

always. His

insistence that “blessing” refers to events that “go against the

ordinary” puzzles me.

Consider that most births are without calamity, but we

still consider a healthy newborn to be a blessing.

I question Marshall’s tone, as well.

His article represents a far too-frequent attitude in the

church and in our society that one ought not simply disagree on

occasion with certain opinions, but also destroy the persons who

hold them. When

combined with careless analysis, such a stance is dangerous to

all concerned, especially in the church.

–Philip Hefner

dialog: A

Journal of Theology

Volume 40, Number 1

• Spring 2001

(Reprinted from the January 20, 2019 Sunday bulletin insert) |

|

Ephesians 3.10

Monthly Home Bible Study, November 2021, Number 345

The Reverend Ronald F. Marshall

Along with our other regular study of

Scripture, let us join as a congregation in this home study. We

will study alone than

talk informally about the assigned verses together as we have

opportunity. In this way we can "gather

together around the

Word" even though physically we will not be getting together

(Acts 13.44). We need to support each other in this

difficult project. In 1851 Kierkegaard wrote that the Bible is

"an extremely dangerous book.... [because] it is an imperious

book... – it takes the whole man and may suddenly and radically

change... life on a prodigious scale" (For

Self-Examination). And in 1967 Thomas Merton wrote that "we

all instinctively know that it is dangerous to become involved

in the Bible" (Opening

the Bible). Indeed this word "kills" us (Hosea 6.5) because

we are "a rebellious people" (Isaiah 30.9)! As Lutherans,

however, we are still to "abide in the womb of the Word" (Luther's

Works 17.93) by constantly "ruminating on the Word" (LW

30.219) so that we may "become like the Word" (LW

29.155) by thinking "in the way Scripture does" (LW

25.261). Before you study, then, pray: "Blessed Lord, who caused

all holy Scriptures to be written for our learning: Grant us so

to hear them, read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest them, that

we may embrace and ever hold fast the blessed hope of

everlasting life, which you have given us in Our Savior Jesus

Christ. Amen" (quoted in R. F. Marshall,

Making A New World: How

Lutherans Read the Bible, 2003, p. 12).

Week II.

Read again Ephesians 3.10 noting the same word

church. What purpose

does the church serve? On this read 1 Timothy 3.15 noting the

concept bulwark of truth.

What is the truth? On this read John 6.68 noting the line

words of eternal life.

What are these words? On this read also John 3.19 noting the

words judgment,

light,

loved,

darkness,

light and

evil. What is the

impression left by this verse? On this read Isaiah 1.6 noting

the line from the sole of

the foot even to the head, there is no soundness. Read also

Luke 13.3 noting the words

repent and

perish. How does one

repent? On this read Psalm 51.17 noting the words

broken,

contrite,

heart,

God and

despise. Then read

Romans 5.8-9 noting the words

God,

love,

yet,

sinners,

Christ,

died,

justified,

saved,

blood and

wrath. How does Jesus

bloody death do this for us sinners? On this read Galatians 3.13

noting the three occurrences of the word

curse and also

Colossians 2.13-14 noting the words

dead,

trespasses,

God,

alive,

forgiven,

canceled,

bond,

against,

us,

legal,

demands,

set,

aside,

nailing and

cross. Finally read

Romans 3.25, Hebrews 11.1-6 and 2 Peter 1.5-11, noting the many

occurrences of the word

faith. So what is this truth about sin, salvation and faith

that comes from the Lord God Almighty?

Week III.

Reread Ephesians 3.10 noting the word

through. Why does

this happen only through the church and not through, for

instance, recreation, entertainment, education, art or politics?

On this read Ephesians 3.12 noting the word

access. Why is this

limitation imposed? On this read Colossians 1.20 noting the

words reconcile,

peace,

blood and

cross. Access to God

is therefore limited to Christ Jesus because he alone has

overcome the hostility between God and human beings. But why

can’t Jesus’ work of reconciliation be extended to all other

modes of access? On this read Luke 3.22 noting the line

with you I am well

pleased. This says that God has bound himself to Jesus and

no one else – so he cannot share his access with others in whom

God is not well pleased. How can this be promoted while at the

same time avoiding being

haughty as Romans 12.16 says?

Week IV.

Read Ephesians 3.10 one last time noting the term

manifold wisdom. What

is this wisdom and how does the church promote it? On this read

Ephesians 1.17-23 noting the words

wisdom,

Christ,

above,

all,

authority,

power,

head and

church. Is this

manifold wisdom Christ’s rule over all matters in life and

faith? If so, how is this practiced in the church? On this read

Philippians 3.7-11 noting the words

gain,

loss,

surpassing,

worth,

refuse,

righteousness,

not,

own,

faith,

share,

sufferings and

if. What is the drift

of these verses? First, worldly prosperity is not our goal. Next

self-effacing humility is. Finally the easy life free of

suffering and personal uncertainty is wrongheaded. Do these

verses fit in with the

hard, narrow way

in Matthew 7.14? If so, in what ways?

|

|

Announcements

Sunday

Worship ― online at www.flcws.org.

We continue to offer

these abbreviated online liturgies weekly for those unable to

make it to church on Sunday. In

them we are spending our time apart to accentuate Psalm 46:10

about being silent before God.

HOME COMMUNION:

Holy Communion is available for home use for those who are not

able to come to church.

If interested, please call 206-935-6530 or email the

office at

flcws.fd@gmail.com.

PLEDGE CARDS:

Please plan to return your pledge card as soon as possible or

before Monday, the 8th of November.

FOOD BANK COLLECTION

suggested donation for November is holiday foods: turkey, gravy,

cranberries, stuffing, potatoes and pumpkin.

COMPASS HOUSING ALLIANCE:

Until the middle of December, we

are collecting Christmas gift items for the Compass Center for

both men and women.

Some suggested items needed are: Amazon, Target, Fred Meyer and

Walmart gift cards in $25 increments; men’s slippers size 9 &

above, women’s PJ sets size L-3X, 39 hot/cold thermoses, at

least 12 oz., 25 sets of dishware.

Donations can be left at the church office.

100TH ANNIVERSARY BOOK:

The 100th Anniversary

Book is available for purchase.

There is a sample book for you to look at if you wish

before purchase.

The cost is $26 each, which covers the cost of the printing.

Please make your check out to FLCWS with the designation

of 100th Anniversary Book.

The books can be found on the Narthex counter most

Sundays, unless they’ve sold out.

More will be on order.

These books can also be ordered through the church office

by calling (206) 935-6530.

If the office is closed you can leave a message and we’ll

get back with you.

Also, the office email is

flcws.fd@gmail.com.

2021 FLOWER CHART:

A

few more people signing up for Christmas flowers would be

helpful.

Wednesday/THURSDAY Evening Bible ClassES:

All

Bible classes have been put on hold until Pastor Marshall is out

of hospital and able to resume his schedule.

|

|

|

|

________________________________

CHRIST THE KING:

The season of Pentecost and

the

Church Year will end with the celebration of the

Kingship

of Christ at the Sunday morning liturgy

on

November 21st.

On this day we strengthen the belief that Christ is above all

and that every authority is under Him (Eph. 1:21).

We rejoice that the

One

who is, who was and is to come (Rev. 1:8) is the King and Lord

of all!

ADVENT I

Sunday, November 28th

|

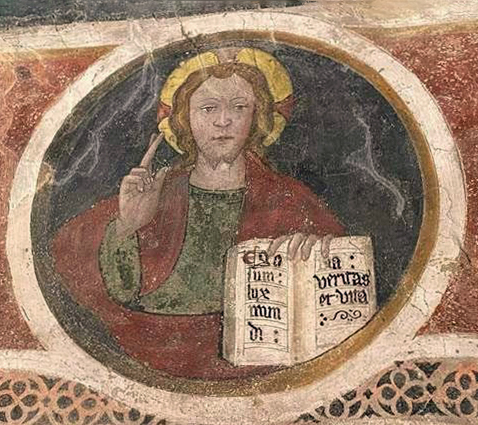

Fenis Castle, Aosta, Italy –

courtesy, Dr. Mark Bertness.

|

|

The Rev. Ronald F. Marshall, Jane Harty and

family, Kim

Lim, Melanie Johnson, Holly Petersen, The Nancy Lawson Family,

Leah and Melissa Baker, Felicia Wells, Marlis Ormiston, Connor

Bisticas, Eileen & Dave Nestoss, Kyra Stromberg, Tabitha

Anderson, The Rev. Randy Olson,

The Rev. Albin

Fogelquist, The Rev. Howard Fosser, The Rev. Alan Gardner, The

Rev. Allen Bidne, Leslie Hicks, Kari Meier,

Yuriko

Nishimura, Eric Baxter, Lesa Christiansen, Richard

Patishnock, Ty Wick, Anthony Brisbane, Susan Curry, Robert Shull

family, Alan Morgan family, Lucy Shearer, Ramona King, Karen

Berg, Donna & Grover Mullen and family, Kurt Weigel, Carol

Estes, Paul Jensen, Tak On Wong & Chee Li Ma, Hank Schmitt, Mary

Ford, Andrea and Hayden Cantu, Dana Gallaher, Jeanne Pantone,

Kevan & Jackie Johnson, Trudy Kelly, Eric Peterson, Gary Grape,

Larry & Diane Johnson, Wendy & Michael Luttinen, the Olegario

Family, Nita Goedert, Mariss Ulmanis, Shirley & Glenn Graham,

Karen Granger, Mike Nacewicz, Mike Matsunaga, Bill & Margaret

Whithumn, The Robert Shull family, Mary Cardona, and

Grace-Calvary Episcopal Church (Clarkesville, GA).

Pray for our professional Health

Care Providers:

Gina Allen, Janine Douglass, David Juhl, Dana

Kahn, Dean Riskedahl, Jane Collins

and all those

suffering from the coronavirus pandemic. Pray for our country, for unbelievers, the addicted, the sexually abused and harassed, the homeless, the hungry and the unemployed.

Pray for the shut-ins that the light of Christ may give them

joy: Gregg &

Jeannine Lingle, Bob

& Mona Ayer, Joan Olson, Bob Schorn, C.J. Christian, Crystal

Tudor, Nora Vanhala, Martin Nygaard.

Pray for our bishops Elizabeth Eaton and Shelly Bryan Wee, our

pastor Ronald Marshall, our choirmaster Dean Hard and our cantor

Andrew King, that they may be strengthened in faith, love and

the holy office to which they have been called.

Pray that God would give us hearts which find joy in service and

in celebration of stewardship.

Pray that God would work within you to become a good

steward of your time, your talents and finances.

Pray to strengthen the stewardship of our congregation in

these same ways.

Pray for the hungry, ignored, abused, and homeless this

November. Pray for

the mercy of God for these people, and for all in Christ's

church to see and help those who are in distress.

Pray for our sister congregation:

El Camino de Emmaus in the Skagit Valley that God may

bless and strengthen their ministry.

Also, pray for our parish and its ministry.

Pray that God will bless you through the lives of the saints:

Saint Andrew, the Apostle.

Pray for this poor, fallen human

race that God would have mercy on us all.

Pray for this planet, our home,

that it and the creatures on it would be saved from destruction. |

|

A Treasury of Prayers O Lord,

blot out, we beseech thee, the transgressions that are against

us, for thy goodness and thy glory, and for the sake of thy Son

our Savior Jesus Christ. Amen. [For All the Saints II:1248, altered] |