Sermon 56

Beware of

Sin

John 9:3

February 24,

2008

Sisters and

brothers in Christ, grace and peace to you, in the name of God the

Father, Son (X)

and Holy Spirit. Amen.

The famous verse about sin in John 9:3 is before us today. It says that the man born blind wasn’t at fault – nor were his parents. In fact it doesn’t seem to care about what caused his blindness at all. All that seems to matter is that Jesus heals him and shows forth his glory by miraculously bringing this about. And that’s it.

Mere

Accidents

On this view, blindness – and all suffering, illness, injury, and the many calamities of life – are only accidents. They don’t happen to us because we’ve sinned and deserve them. They aren’t punishments for the sins we’ve committed. No, when we, for instance, get sick, all that’s happening is that we have caught some germ floating around in the air – quite aimlessly. And that happens because we were in the wrong place when someone sneezed on us.

Now while many Christians today believe something similar to this accidental view of suffering (see F. Lindström, Suffering and Sin, 1994) – it isn’t the Biblical view by any stretch of the imagination! That’s because this accidental view cuts off the effects of sin. When we sin – according to this lesser view of suffering – no ripple effects radiate out from our sin to harm us. No, sin simply happens and then it’s over. And nothing more – unless, of course, a crime has been committed and the courts get involved.

Accentuating Sin

So on this accidental view of suffering, we see that sin is minimized. Sins are simply to be weathered and forgotten. Anything else would be a waste. But not so in the Biblical view. There sins are to be accentuated – and not glibly set aside. By way of the law of God, sin is to be made as sinful as possible – even “beyond measure” (Romans 7:13) or supra modum, as the old Latin Bible has it. We are to accentuate sin to the hilt – even to the point of appearing unreasonable – supra modum! Because sin is so damaging (Ecclesiastes 9:18), we need to understand it clearly if we are going to thwart it (Romans 6:17-18). And making it sinful beyond measure guarantees that we won’t under estimate its effects and end up becoming helpless before it because we have misread it.

Martin Luther (1483-1546) – our most eminent teacher [The Book of Concord (1580), ed. T. Tappert (1959) p. 575], didn’t minimize sin. He didn’t think we should sweep it under the carpet – but instead directly feel its bite (Luther’s Works 8:6) and thereby see that it’s even “worse than death” itself (LW 52:279). In fact,

it is not possible to make the mercy of God large and good, unless a person first makes his miseries large and evil or recognize them to be such. To make God’s mercy great is not, as is commonly supposed, to think that God considers sins as small or that He does not punish them.... Hence our total concern must be to magnify and aggravate our sins (LW 10:368).

Since it’s so difficult to accept this horrifying or “rough truth” (LW 11:58) about us, sin must be stressed more than grace and the comforting aspects of our life with God (LW 11:274). And if any of us were to refuse to listen to this bad news, all we would then deserve is to have the law preached at us [Sermons of Martin Luther, 8 vols, ed. J. Lenker (1988) 4:160]. These are harrowing words – but still true! In fact, the sin that we’re born with is so deep and devastating that it can’t “be recognized by a rational process, but only from God’s Word” (BC, p. 467)! And that word drives us to admit that we are “mighty sinners” (LW 48:282).

Visiting the Sick

Because of

Luther’s severe, Biblical view of sin, he had a more ominous, upsetting

and unpopular way to visit the sick. In Doberstein’s classic

Minister’s Prayerbook (1959,

1986), we read about the way Luther visited the sick:

When Dr.

Luther came to visit a sick man, he spoke to him in a very friendly

manner, greeted him very warmly.... Then he began to inquire whether

during this illness he had been patient towards God. And after he had

discovered how the sick man had borne himself while sick, and that he

wished to bear his affliction patiently, because God had sent it upon

him out of his fatherly goodness and mercy, and that... by his sins he

had deserved such [sickness], and that he was willing to die if it

pleased God to take him – then he... praised this Christian disposition

as the work of the Holy Ghost,.... admonished him to [remain] steadfast

in this faith,.... and promised [to] pray for him (p. 367).

Few pastors

visit the sick like that any more – and you can rest assured of that!

But Luther is still right on how he goes about his visits to the sick.

For if sin is the cause of our suffering, then it would be positively

cruel not to address the root of our problem. But when Luther wades into

these deep and dangerous waters, he does so with kindness. Once the

connection to sin is established and accepted, he praises the patient

for the Christian attitude God has so graciously given him. No

brow-beating. No condemnation. No ridiculing. All we have is sober

confession – and abiding hope.

The Lutheran Rule

Given this

pastoral account of how the sick should be visited, it would make sense

to formulate a theological rule based on this tight connection between

sin and suffering – which is in fact what the Lutheran Confessions have

done. There we read:

As a

rule,... troubles are punishments for sin. [But] in the godly they have

another and better purpose, that is, to exercise them so that in their

temptations they may learn to seek God’s help and to acknowledge the

unbelief in their hearts.... Troubles are [also] a discipline by which

God exercises the saints. So troubles are inflicted on account of

present sin because in the saints they kill and wipe out lust so that

the Spirit may renew them (BC,

p. 206).

This is a

chilling rule – but not without its blessings. For it also points out

that punishments can be salutary and good for us by warning us, as well

as by strengthening us (1 Corinthians 10:6).

John 5:14

Lutherans

didn’t make up this rule – since it directly comes from the Holy Bible

itself. For instance, in John 5:14 Jesus tells the crippled man he

heals: Go and “sin no more that nothing worse befall you.” It’s

noteworthy that the critical wizard of the New Testament, Rudolf

Bultmann (1884-1976) by name, doesn’t try to deny that we have

retribution in this verse, or the view that sickness comes from sin. And

furthermore, he goes on to say that the down-playing of the cause of

suffering which we see in John 9:3, doesn’t undercut the retribution

that’s in John 5:14 [The Gospel

of John (1971) pp. 243, 331]. The reason for this is that the two

passages only appear to be in conflict with each other. For John 5:14

explains where the suffering comes from, and John 9:3 shows how Jesus

will do away with it. So what appears to be contradictory actually isn’t

at all. In fact, these two verses actually work together – and

coherently at that – for they address different aspects of the same

problem, rather than opposing sides of the same problem. This simple

clarification puts the lie to this alleged contradiction.

So in Galatians 6:7 we’re rightly told that we’ll reap what we

sow – for unaddressed sin leads ineluctably to all sorts of troubles in

our lives. Galatians 6:7, then, tells us the same thing that John 5:14

does – that it’s “not safe to run up against” God (LW

33:34), for he won’t sit by idly when we mock him! For there is a causal

nexus in the universe through which past deeds bear upon future events

(Genesis 2:17, 4:10) – and so, because of that, it’s reasonable to

suppose that we do indeed reap what we sow. And to deny this nexus is to

mock God – and that we would do at our own peril for God is firm about

punishing wrongdoers (Hebrews 10:30).

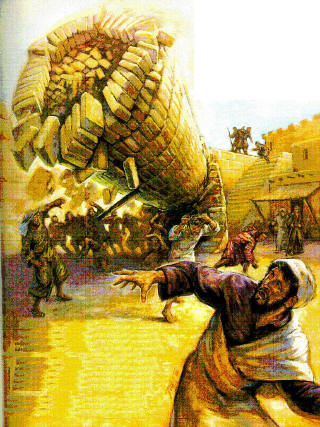

The Tower in Siloam

Now the

famous collapse of the tower in Siloam in Luke 13:4-5 also undergirds

this deeply embedded moral nexus. In this passage Jesus says that the

eighteen who died under the weight of that fallen tower weren’t worse

sinner than those who escaped. Nevertheless whoever doesn’t repent of

their sins will also get struck down mercilessly. The point, then, isn’t

that unrepentant sin is harmless since Jesus doesn’t say that the ones

who died were worse off [contra

D. B. Hart., The Doors of the

Sea: Where Was God in the Tsunami? (2005) p. 31]. No, the plain

meaning of the text is – “He yesterday, I today” (LW

9:103). For no one is exempt, since all have sinned (Romans 3:23), and

all careless sinners will be punished (LW

33:35) – when God’s ready (Jeremiah 6:15).

But when we hear in the news that those who suffer had it coming,

so to speak, we wince at this crude and simplistic reasoning. We’re

shocked when the imam said that the over 200,000 Muslims who died in the

2004 Indian Ocean earthquake were being punished by Allah for their

ongoing civil war (Bill Broadway, “Divining a Reason for Devastation,”

Washington Post, January 8,

2005). So too when Pat Robertson said that the over 1800 who died in the

2005 flood in New Orleans were being punished for the moral turpitude of

their city, known as The Big Easy for to its lax moral standards (Reed &

Reed, Unnatural Disaster,

2006).

Nevertheless, these charges are not altogether unfounded, as

surprising as that may sound. So we can’t say, with any integrity, “no

to any system at all that uses suffering to prove things” [contra

Rowan Williams, Writing in the

Dust: After September 11 (2002) p. 71]. This is in large part

because it can be responsibility shown that [Peter van Inwagen,

The Problem of Evil (2006)

p.111]

there can be

cases in which it is morally permissible for an agent to permit an evil

that agent could have prevented, despite the fact that no good is

achieved by doing so.... [And] that is exactly the moral structure of

the situation in which God finds himself when he contemplates the world

of horrors that is the consequence of humanity’s separation from him.

On this

score it would be unrealistic, as well as unfaithful, to deny that we

suffer because we have sinned – and that “misfortunes do not come from

God at all” [Harold S. Kushner,

When Bad Things Happen to Good People (1981) p. 44]. For “sin is

sin, and by its nature it merits punishment” (LW

12:333)! So the fact that some evildoers seem to escape punishment is no

reason to believe that God doesn’t punish sin – but only that he

shrewdly punishes sin unevenly (LW

28:159-160). Luther, then, has it right – in what he teaches children in

his Small Catechism (1529) –

that because we “sin daily, [we] deserve nothing but punishment” (BC,

p. 347). So when “plague, war, famine, fire, flood,... and troubles of

every kind” befall us, “we get what we deserve” (BC,

p. 372)! In general this is true, even though specific people and

detailed infractions and faults cannot always be accurately pinned down

to everyone’s complete satisfaction. But that should never be used to

invalidate the truth that when, for instance, “a deadly epidemic

strikes,... God’s punishment has come upon us” (LW

43:127).

Punished in Our Place

Now how are

to live with this terrifying moral nexus that shows our sins causing our

sufferings? The moral burden in this connection is too much for us

(Romans 1:27). Because of that we cannot control our urge to deny,

refute or otherwise blast apart everything about this connection between

sin and suffering. What shall we then do? Are we doomed to despair and

eternal damnation?

Left to ourselves, we clearly would be – loving the darkness as

we do (John 3:19). But there’s more. Mercifully there is something

greater than ourselves to save us from ourselves (1 John 3:20). But this

will require of us to be “adults in our thinking” (1 Corinthians 14:20).

That’ll mean that we’ll have to ponder more than the simple, linear

lines of Scripture – like “let not your hearts be troubled; believe in

God” (John 14:1), wonderful though they may be. And when we do that,

we’ll find the depths of God’s love (Ephesians 3:18) in the complex

verses of the Bible with dependent, relative clauses that aren’t always

easy to get (2 Peter 3:16).

Take, for instance, the complex passage in 2 Corinthians 5:17-21

– with it’s sterling, liberating good news:

For the love

of Christ controls us, because we are convinced that one has died for

all; therefore all have died. And he died for all, that those who live

might live no longer for themselves but for him who for their sake died

and was raised.... For our sake God made Christ to be sin who knew no

sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God.

This complex

passage has four logical connectors – because, therefore, but, and so

that – along with four relative, dependent clauses to complicate

matters. But its meaning isn’t lost on us for all of that – only harder

to get at. So take it from the beginning – the love of Christ controls

us. With that clear, simple line at the beginning, we get off on the

right foot. We who cannot control ourselves are given a gift – Christ

himself will control us. And in this word we have a hope we can find

nowhere else.

But how does his love control us? This happens through his dying

for us. On the cross he is inflicted with all the sins of the world (1

Peter 2:24) – that he might be punished for them in our place (LW

26:283-284). Because of his death, then, we’re saved from being punished

in hell forever (Luke 16:26). This, then, makes Christ our grand

substitute, standing in our place –

Ich trit an deine stat (LW

22:167)! Doing this for us shows his monumental love for us – while we

were yet sinners (Romans 5:8). And so, like the soldier at the cross –

aiding and abetting the crucifixion of Christ, we’re overwhelmed with a

love for Jesus, having seen his love for us (Matthew 27:54; Luke 23:47).

And in precisely just this way, his love controls us – and draws us to

himself (John 6:44, 12:32). Luther calls this teaching an “astounding

doctrine”:

Only...

Christ frees us..... One has sinned, another bears the punishment....

One has sinned, Another has made satisfaction. The sinner does not make

satisfaction; the Satisfier does not sin (LW

17:99)

Through this faith in and love for Christ, our sins are forgiven,

and we’re given power (John 1:12) to fight the good fight of faith (1

Timothy 6:12; Romans 6:15) against the sins that continue to pester us –

like being “irascible, spiteful, envious, unchaste, greedy, lazy,

proud,... and unbelieving” (BC,

p. 445).

So come and receive Christ today – the one who shed his blood to

save you. He is in the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper – at the altar of

our Lord. Come and bow down and eat of the bread and drink from the cup

that life might well up in you (John 6:53).

Praying for the Sick

And know

also that this wonderful gift is given that we might do good works

(Ephesians 2:10). For as we know, faith without works is dead (James

2:26) – since faith needs “supplementing” with good deeds (2 Peter 1:5).

On this day, then, let us who believe in Christ, do good works in his

name (Colossians 3:17). And let our good work be the redoubling of our

efforts in praying for the sick and injured (Matthew 6:6; Luke 18:1).

But if sickness and other calamities are punishments for our

sins, then why try to interrupt those punishments by praying to God for

healing and relief (James 5:14)? And why, for that matter, does Jesus

even bother to heal the sick – saying that their faith has made them

well (Matthew 9:22, 15:28; 17:21)? Or, if death is the most severe

punishment of all for our sins (Romans 6:23;

LW 13:98), then why does God

raise the dead just so they can live longer on earth (1 Kings 17:22; 2

Kings 4:34; Mark 9:27; Luke 8:55; John 11:44)? Well, the short answer to

all of these questions is because God says he wants us to pray for the

needy (LW 24:388) – and

without ceasing (1 Thessalonians 5:17). Period.

But the longer answer is that while our sins do indeed provoke

God’s anger against us (Deuteronomy 4:25; Judges 2:12; Jeremiah 11:17),

he nevertheless still abounds in steadfast love (Exodus 34:6; Nehemiah

9:17; Psalm 145:8; Joel 2:13; Jonah 4:2). So “his anger is... for a

moment, [but] his favor is for a lifetime” (Psalm 30:5;

LW 8:73). Let not our proper,

Biblical understanding of sin, suffering and punishment, then, thwart

our prayers for the sick, the injured, and the destitute. Know that the

Lord’s punishments do not cancel his abiding grace and favor – therefore

never “lose courage when you are punished by him” (Hebrews 12:5).

Even so, don’t obsess over your healing – desperately hanging on

to this life, regardless of the quality of it [see Stanley Hauerwas,

God, Medicine, and Suffering

(1990, 2003) pp. 36-37, 62-64, 78, 89, 114, 150]. Know instead, that

heaven is your home (Philippians 3:20) and that we are only sojourners

here – just passing through (Psalms 119:19; 1 Peter 2:11). And then,

given this warning, may our good work still be to pray for the sick and

the broken (Luke 4:18, 10:37) – even though we’ve seen in a compelling

way the clear and intricate connection between sin and suffering, which

the accidental view is blind to (Matthew 10:29). Amen.

(printed as preached but with a

few changes)