Come to Your

Senses!

Luke 15:17

March 14,

2010

Sisters and

brothers in Christ, grace and peace to you, in the name of God the

Father, Son (X)

and Holy Spirit. Amen.

Today we have before us the famous Parable of the Prodigal Son – perhaps the best known parable of Jesus, next to the one on the good Samaritan (Luke 10:30-37). This parable on the prodigal son is great – inspiring the text of the beloved hymn, Amazing Grace, by John Newton (1725-1807), and also the radio humorist, Garrison Keillor, to say that the only eulogy he wants read at his funeral is this parable (The Lutheran, February 2002, p. 22).

The Prodigal

Son

This parable is also internally great for its three leading figures – the woebegone son, after whom it’s named, and then the forgiving father and jealous older brother. The famous German Lutheran scholar, Helmut Thielicke (1908-1986), argued in his popular book, The Waiting Father (1959), that this parable should actually be named after the father since it’s “only because... [he] was open and receptive... that [the son] was able to... be reconciled” (p. 28). But that’s not quite right. For if that naughty boy hadn’t repented of his dissolute, “loose” (RSV) or “riotous” (KJV) ways (Luke 15:13) – he never would have gone home to look for reconciliation with his father in the first place. On that score, then, the younger, disobedient son is the key figure – as has been said for years – because repentance is so central to forgiveness – as Martin Luther (1483-1546) long ago pointed out, calling it in fact a requirement of forgiveness itself (Luther’s Works 12:333).

So the

heart of this parable then is the line that “he came to himself” (Luke

15:17). That’s because this line is a euphemism for repentance. When the

younger son comes to his senses he realizes how wrong he is – and that

starts the ball rolling in the direction of his new life (Luke 15:24,

32). But many don’t see it that way. Barbara Grace Witten has written a

whole book on this theological rebellion, entitled

All Is Forgiven (

Reversus

In the old Latin Bible our key line from Luke 15:17, “he comes to himself,” is given a helpful twist – in se autem reversus. Here the note of reversal is sounded – with the putting of pressure on the boy to repent and live a new life. This is illuminating because it captures what’s so difficult about repenting. Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) – that avid reader of Luther’s sermons – expresses this reversus and its inherent internal turmoil in a memorable way. “Only in this way is... the struggle the truth,” he writes. “when the single individual fights for himself with himself within himself” (Kierkegaard’s Writings 5:143). It’s just that sort of inner battle that brings about the reversus of repentance and our new life with God – whereby we admit he’s right and we’re wrong (LW 51:318).

And all of us need to learn from this reversus – because all Christians are threatened by drifting away from our great salvation (Hebrews 2:1-3). Once we’ve been saved by grace through faith (Ephesians 2:8) – we can still make a shipwreck of our salvation (1 Timothy 1:19). So when we’re told that nothing can snatch us from our Father’s hand (John 10:29) – that doesn’t mean that we can’t ruin our faith all on our own (contra Luke 11:28; 1 Peter 5:9) (LW 28:252-253; 51:128). For God’s faithfulness doesn’t keep us from being faithless (2 Timothy 2:13). Therefore Lutherans condemn “those who teach that persons who have once become godly cannot fall again” [The Book of Concord (1580), ed. T. Tappert (1959) p. 35]. Because of that danger and risk we need to “live in harmony” with our baptism and keep it as a “daily” preoccupation (LW 35:39; BC, p. 445) – seeing to it that we’re even converted on a “daily” basis as well [quottidie converti] (LW 17:117).

Sexual Filth

By studying the prodigal son carefully we’ll be able to work more diligently at being converted on a daily basis. And the first thing we learn from such a study is our weakness for sexual filth. In the parable we’re told that he wanted to run off to a far away country so he could have sexual dalliances with whores and not be seen or caught by his family and friends (Luke 15:13, 30). That’s what he spent his fortune on – illicit sexual favors. And that tempts us all.

Just think how advertisers use immodestly clad women to sell nearly anything (T. Reichert & J. Lambiase, Sex in Advertising, 2002)! Or think how the brawny, sexy fireman’s calendars are sold out right away to women of all ages! The prodigal son escaped to that far away place because he refused to be bound by the vows of the holy estate of matrimony. God gives us those confinements in which to express ourselves lovingly and sexually. But we want to burst our bonds asunder (Psalm 2:3)! We refuse the sexual confinements set within the restrictions of the marriage vows – forsaking all others and keeping ourselves only for our husband or wife. This freedom-in-confinement is the glory of Christianity (Romans 6:16-18) and is well-expressed in that all but forgotten hymn by George Matheson (1842-1906), “Make Me a Captive Lord, and Then I Shall Be Free” [Service Book & Hymnal (1958), Hymn 508]. So let us beware and struggle not to make the same mistake.

In

Luther’s Large Catechism

(1529) he tells us that keeping marriage holy will make for “less of the

filthy, dissolute, disorderly conduct which now is so rampant everywhere

in public prostitution and other shameful vices” (BC,

p. 394). This theological conviction is confirmed in anthropological

studies which have shown that humans – if not constrained by the Spirit

of the Lord – are promiscuous like the sexually wild chimpanzees [Jared

Diamond, The Third Chimpanzee

(1992) pp. 25, 70]. This shameful behavior hasn’t abated much over the

last 450 years – but keeps up at its depressing rate (Infidelity:

A Survival Guide, 1998;

Madam: Inside a Nevada Brothel, 2001). Just think of the rampant

prostitution in AIDS-infested, sub-Saharan

The Battleground

These same

sexual allurements – that the prodigal son caved in to – throw us all

into the battle between the spirit and the flesh. The classic Biblical

passage on this struggle is in Galatians 5:16-24:

Walk by the

Spirit and do not gratify the desires of the flesh. For the desires of

the flesh are against the Spirit, and the desires of the Spirit are

against the flesh; for these are opposed to each other, to prevent you

from doing what you would.... Now the works of the flesh are plain:

fornication, impurity, licentiousness.... But the fruit of the Spirit

is... patience,... faithfulness,... self-control.... Those who belong to

Christ Jesus have crucified the flesh with its passions and desires.

On this

battlefield we learn that flesh and Spirit don’t co-exist together

peacefully. So if it feels good – that doesn’t mean you should do it, as

that old mantra from the Summer of Love in 1967 had it. No! we are to

crucify the flesh instead with its passions and desires rather than

simply giving in to them. Those wayward desires always make it look like

the grass is greener on the other side of the hill. But that’s a lie –

and that’s why there’s an adage against it. What’s on the other side of

the hill is actually only a herd of pigs eating their slop. That’s what

the prodigal son found out the hard way. So heed the wisdom of the Lord.

See in the licentiousness of the flesh, destruction and gloom – rather

than some garden of delights. And see in the patience and self-control

of the Spirit, life and freedom – rather than drudgery and despair.

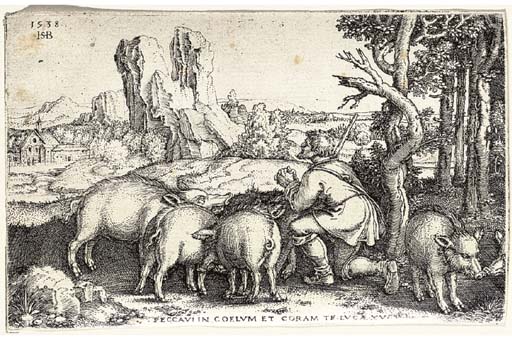

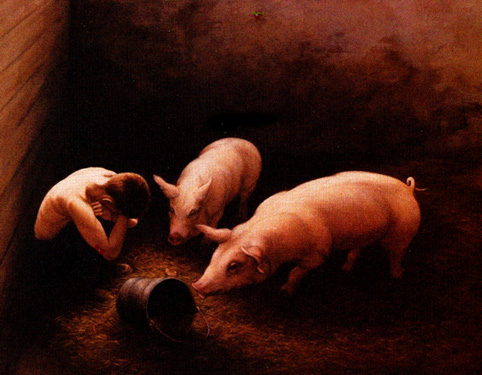

Nose to Nose With Pigs

The prodigal

son turns away from his dissolute life and sexual filth when he

bottoms-out – finding himself starving while feeding the pigs their

slop. At that moment of degradation and humiliation and despair, he

comes to his senses. This is our second lesson to learn from this

parable. It tells us that we’ll continue in our sin as long as we wallow

in its deceits and passing pleasures (Hebrews 3:13, 11:25). But once

we’ve been cut to the quick (Acts 2:37), then our eyes will be opened.

It’s as if some one had grabbed us and shook us until we come to our

senses and discover how we’ve hurt ourselves. That’s exactly what

extreme situations are for. They clear the fog so we can see what’s

going on. That’s why we’re told that no one will enter the

So the

Lutheran Confessions rightly teach that the prophet Isaiah in Isaiah

28:21

calls it

God’s alien work to terrify because God’s own proper work is to quicken

and console. But he terrifies, he says, to make room for consolation and

quickening because hearts that do not feel God’s wrath in their smugness

spurn consolation (BC, p.

189).

Luther

famously called this terrifying quickening being “driven to Christ” or

agitatur ad Christum (LW

16:232). Furthermore he writes (Sermons

of Martin Luther, ed. J. Lenker, 3:130) that

the

righteous, while they live here, have flesh and blood, in which sin is

rooted. To suppress this sin God will lead them into great misery and

anxiety, poverty, persecution and all kinds of danger... until the flesh

becomes completely subject to the Spirit. That, however, does not take

place until death...

Well the

prodigal son found out about this great misery and anxiety, poverty and

all kinds of danger – and so shall we when we sally off to some far

place for our dabbling in dissolute delights!

No Excuses

Finally mark

well what the prodigal son said when he repented. He doesn’t blame his

father for giving him his inheritance too soon – before he was mature

enough to handle it (Luke 15:12). No, he heaps all the blame upon

himself. Nor does he blame the women he abused for sexually selling

themselves to him. No, he takes all the blame himself.

Mea culpa,

mea culpa,

mea

maxima

culpa he cries – “by my most

grievous fault” he bewails his sins [Lutheran

Book of Worship (1979) p. 155]. So he emphatically resolves (Luke

15:19) that he must go and tell his father that

I have

sinned against heaven and before you; I am no longer worthy to be called

your son; treat me as one of your hired servants.

And so he

grovels in abject self-abasement – and rightly so for he has been

willfully and defiantly reveling in sexual filth and deep rebellion. Now

all excuses have come to an end (Luke 14:18; B. Cosby & A. Poussaint,

Come On, People: On the Path from

Victims to Victors, 2007; A. Dershowitz,

The Abuse Excuse, 1994). Now

all explanations of extenuating circumstances count for nothing. Now he

must confess his sins in contrite repentance and nothing more. For only

that will do. Anything else – God will surely despise (Psalm 51:17). So

learn this lesson well from the prodigal son. Don’t try to defend

yourself before the Almighty God – for that would be nothing more than

demonic (LW 22:397)! But

instead simply say, “God, be merciful to me a sinner!” (Luke 18:13).

Knowing How It Ends

But what if

the spirit is willing but the flesh is weak (Mathew 26:41)? What then?

What if we can’t muster the

reversus of the prodigal son? What if that act of self-accusation

seems like a super-human feat for us? What then? Are we finished off?

Are we doomed to an eternity of eating slop with the pigs?

No! for

we have more than the prodigal son had in that distant land where he

found himself wallowing in dissolute ways. We have the whole parable

before us. We know how it all ends. We have seen his father running to

him, embracing him and kissing him – while he was still far off (Luke

15:20). And that picture pulls us ahead. It can do for us what we cannot

do for ourselves (John 6:44; Romans 8:3). It changes us from within (2

Corinthians 3:18). It gives us hope – hope in someone other than our

sinful selves (Hebrews 12:2). From our perspective the weakness of the

prodigal son seems awfully mighty to us. Why does he pick himself up and

go home in shame and not just die in the pig sty? How does he summon the

strength to pivot around like that – in the slippery mud and in the

obsessive filth? Well, we don’t have to spend too much time on that –

wondering if we could do the same.

And

that’s because we know about God’s love for us in Christ Jesus. In

Christ Jesus, God’s love for us is not unpredictable and uneven. In him

God’s love for us is sealed (John 6:27) – that is to say, it is certain

and nothing we can do or will do will be able to dislodge it. And that’s

because his love for us is not grounded in our lovability (LW

31:57; 30:30) – but in the fact that he sent his only Son Jesus Christ

to be a sacrifice for our sins (1 John 4:10).

Keeping the Cross in the Parable

We have been

warned that the church has within it those who are enemies of the cross

of Christ and who will try to empty it of its power (Philippians 3:18; 1

Corinthians 1:17). And it’s no different now. Today there are those

trying to use this profound parable of the prodigal son to show how God

doesn’t need Christ Jesus to die for us so that he can love us [M.

Winter, The Atonement (1995)

p. 89; The Nature of the

Atonement, ed. Beilby & Eddy (2006) p. 104]. On this view grace

doesn’t have to wait for the crucifixion before it can be lavished upon

us (contra John 1:17, 19:30;

Ephesians 1:7-8). That’s because the father loves the prodigal son

without any intervening sacrifice being made (contra

BC, pp. 414, 541, 550, 561) –

nor, for that matter, with any repayment of his squandered inheritance

being made. He simply sees him coming home and welcomes him lovingly.

Nothing more happens – nor is needed to happen. And all of that is

because God is simply love (1 John 4:8). No miraculous, divine sacrifice

is needed “to move God to mercy” (contra

LW 51:277). He just loves us

– pure and simple.

But this

revision of Christianity and Holy Scriptures is a travesty, designed to

drive a wedge between this glorious parable and the death of Christ on

Why else did

Christ die, except to pay for our sins and to purchase grace for us [so

that God, for his sake, could] forgive us our sins? (LW

52:253).

Indeed, all

other suppositions are false. That’s because they’re built on a

disregard of Christianity [H. Richard Niebuhr,

The Kingdom of God in America

(1937) p. 193] which vainly supposes that

a God

without wrath brought men without sin into a kingdom without judgment

through the ministrations of a Christ without a cross.

Foreswear

all such perversions! Rejoice in the cross of Christ instead (Galatians

6:14) – which undergirds the love of God in this parable. Rejoice and

come to the altar today – to receive the bread and wine of the Lord’s

Supper, for the newness of life (John 6:53).

Fearing Food

And then,

for the good work which faith requires, continue to fast in Lent – that

you may draw closer to God, and he to you (James 4:8). Do that being

guided by the Lutheran Confessions which say that fasting is a

“spiritual exercise of fear and faith” (BC,

p. 221).

So

register the fear of food – noting its dangers. For we’re often out of

balance – either due to stuffing ourselves or starving ourselves [C.

Costin, The Eating Disorders

Sourcebook, 1996, 2007; Allhoff & Monroe,

Food & Philosophy, 2007].

This might be because we’re “first of all bodies” and only second of all

minds [P. Sponheim, Faith &

Process (1979) p. 176]. So because of that bodily hazard, be more

serious about controlling yourselves by fasting. Don’t under-estimate

food. By eating of the forbidden tree, we lost paradise (Genesis 3:6);

and by eating of the miraculous loaves, Christ was obscured (John

6:26-27). So beware. Fear food that you might fast and fight against the

hold it has on us.

But also

note that this discipline needs faith. So call on God for help – that

you might also keep your senses about you. Amen.

|