Sermon 74

Labor for Love

1 Thessalonians 1:3

November 13, 2011

Beloved in the

Lord, grace and peace to you, in the name of God the Father, Son (X)

and Holy Spirit. Amen.

Bad Sentimentality

And that labor is good because it also

teaches us how to love as Christ did (John 15:12). Now the one whom I

believe has written most cogently and faithfully on this topic is Søren

Kierkegaard (1813-1855) whom we commemorate today [Lutheran

Book of Worship (1978) p. 12]. In his big book, aptly entitled,

Works of Love (1847), where

he celebrates Christian love, he gives us many helpful insights. There he

battles against sentimentality and ease in matters of love (Kierkegaard’s

Writings 16:376) – much like

But rather than letting that deter us, let us instead simply move steadily forward with Kierkegaard’s Works of Love – as Martin Luther (1483-1546) might well advise us to do – as he used to do long ago (Luther’s Works 22:305; 52:143; 28:106; 12:388).

Love Gone Awry

So what does he say? At the end of his

book, Kierkegaard writes:

Christianity is [often] presented in a

certain sentimental, almost soft, form of love. It is all love and love;

spare yourself and your flesh and blood; have good days or happy days

without self-concern, because God is Love and Love – nothing at all

about rigorousness must be heard; it must all be the free language and

nature of love. Understood in this way, however, God’s love easily

becomes a fabulous and childish conception, the figure of Christ too

mild and sickly-sweet for it to be true that he was and is an offense,…

that is, as if Christianity were in its dotage (KW

16:376).

In its dotage? Yes indeed! For to reduce

Christianity to sentimentality is to render it senile – thereby

weakening it hopelessly!

Offensive Love

Kierkegaard believes that the only way

to save Christian love from this senility is to have “the possibility of

offense… thoroughly preached back to life again” (KW

16:200). That means seeing how offensive Christian love is. And he shows

this in Works of Love – and

in many ways, with the clearest case coming from 1 Timothy 1:5, where

love is said to be properly at home in the heart or conscience. This

means that love isn’t based fundamentally in the

self-willfulness of drives and

inclination. Because the man belongs first and foremost to God before he

belongs to any relationship…. To drives and inclination this is no doubt

a strange, chilling inversion; yet it is Christianity and no more

chilling than the spirit is in relation to the sensate;… moreover, it is

specifically a quality of the spirit to burn without blazing. Your wife

must first and foremost be to you the neighbor; that she is your wife is

then a more precise specification of your particular relationship to

each other…. Without really being aware of it ourselves, we talk like

pagans about erotic love and friendship, arrange our lives paganly in

that regard, and then add a bit of Christianity about loving the

neighbor (KW 16:140-141).

But that would be to get it all

backwards. Instead we must begin with God and “the spirit’s love,” which

“you cannot point to” – weaning ourselves “from the worldly,” and then

build on that purified, “bound” or “transformed” love (KW

16:146, 145, 149, 139).

So let this witness to the spirit’s love strike you and change

you – with powerful words that “want to lift cars off pinned children,

rescue lost and frozen wanderers – they’d bound out, little whiskey

barrels strapped to their necks” [Ellen Bass,

Mules of Love (2002) p. 65].

But even so they may still sputter and fall flat.

Our Double Mediator

And so we need Christ himself, who in

“madness, humanly speaking,… sacrifices himself – in order to make the

loved ones just as unhappy as himself” (KW

16:111)! But by so doing we not only become unhappy – because we’re no

longer looking to this world for our salvation (1 John 2:15) – but we

also rejoice in the cross of Christ, for “Christianity’s hope is

eternity, and Christ is the Way” (KW

16:248)! For he is our “sacrifice of Atonement” (KW

16:112) – for Christ, as Luther said, “is not the Mediator of one; He is

the Mediator of two who were in the utmost disagreement,… a damned

sinner [and] the wrathful God” (LW

26:325)!

So come, receive him today, for he is here for us in the

sacrament of the Lord’s Supper. But note that this is no ordinary meal –

where “perishable food,” as Luther taught, “is transformed into the body

which eats it.” No, this food is holy – and so it “transforms the person

who eats it into what it is itself” (LW

37:100). So eat and drink, saying with Luther: “I take to myself the

blessed sacrament, when I eat his body and drink his blood as a sign

that I am rid of my sins and… have a gracious God” (LW

51:99)!

Be Merciful

And finally with Kierkegaard, thank God

for the “royal law” (James 2:8) that tells us to love (Matthew 22:39).

Even though this law doesn’t hinge on our insights and efforts (John

15:5; Luke 18:9), but on faith (Ephesians 2:8-10), by which we’re given

the ability so we “can” perform these loving deeds (KW

16:41), it is still holy and good (Romans 7:12). So don’t recoil from

this command as other Lutherans do [contra

S. D. Paulson, Lutheran Theology

(2011) p. 230], but with Kierkegaard, celebrate it, saying:

Wherever the purely human wants to storm

forth, the commandment constrains; wherever the purely human loses

courage, the commandment strengthens; wherever the purely human becomes

tired and sagacious, the commandment inflames and gives wisdom. The

commandment consumes and burns out the unhealthiness in your love, but

through the commandment you will in turn be able to rekindle it when it,

humanly speaking, would cease. Where you think you can easily go your

own way… [or] despairingly want to go your own way, there take the

commandment as counsel; but where you do not know what to do, there the

commandment will counsel so that all turns out well nevertheless (KW

16:43).

No wonder, then, that Luther called the

law “the greatest treasure God has given us” [The

Book of Concord (1588), ed. T. Tappert (1959) p. 411]! Even though

it cannot save us from our sins (Romans 10:4), it surely can help us do

good deeds.

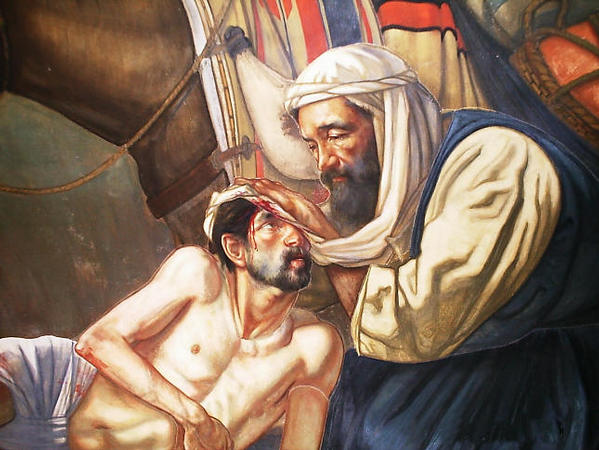

One such good deed is the famous one to be like the Good

Samaritan in showing mercy. “Go and do likewise” (Luke 10:37), Jesus

commands us. And Kierkegaard takes up this charge at the end of

Works of Love. There he reads

it in light of the story about the widow’s mite whose tiny gift into the

temple treasury was deemed “more than” those who put in large sums (Luke

21:1-4):

If… the merciful Samaritan had come not

riding but walking along the road from Jericho to Jerusalem, where he

saw the unfortunate man lying, if he had been carrying with him nothing

[to help him with], if he had carried him to the nearest inn, where the

innkeeper refused [to help because the Samaritan had no money, and if]

the Samaritan… had [then] sought a softer resting place for [him], had

sat by his side,… but the unfortunate one died in his hands – would he

not have been equally merciful? (KW

16:317).

Kierkegaard asks this question to refute

the saying that “mercifulness that is without money [is] a kind of

lunacy, a delusion.” “Therefore,” Kierkegaard goes on to say, “have

mercifulness; then money can be given – without it money smells bad” (KW

16:321).

So “mercifulness works wonders. It makes the two pennies into a

large sum when the poor widow gives them” (KW

16:323). So give it priority! Yet, even so, “the world,” as Kierkegaard

notes, “certainly must think this the most annoying kind of arithmetic,

in which one penny can become so significant” (KW

16:318)! So be not conformed to the world (Romans 12:2) – “keep within

your bosom [a] heart that despite poverty and misery still has sympathy

for the misery of others. [For] if I myself am lying with a broken arm

or leg, then I cannot plunge into the flames to save another’s life –

but I can still be merciful” (KW

16:322, 324). And then, by so doing, you’ll also be laboring to love one

another. Amen.